Artificial Interruption

by Alexander Urbelis (alex@urbel.is)

The Machines of Loving Grace

I'd like to let the readers in on what may, or may not, be a secret about Off The Hook, the weekly radio show on WBAI in New York that Emmanuel hosts and on which I've been a talking head for several years now.

The secret: unless there is a major story we must cover, we have no idea what we will be discussing until the show is live and on the air. The reason for this is that Emmanuel picks and chooses what we will cover and lets the cadence of the show dictate the topics we address. This keeps things feeling organic and unscripted. We must react in real time to news reports from Senegal or Paraguay or whatever far-flung jurisdiction from which Emmanuel has somehow turned up a story about hacking. Daunting as that may be, it is what makes the show honest - much more interesting than stilted podcasts comprised of prepared statements.

Occasionally, it's quite fun to turn the tables on Emmanuel and put him on the spot for a change. We did this on the January 24, 2024 show. Emmanuel opened the discussion by asking whether anyone had anything new to report. I did. Earlier that day, I was on the phone with Virgil Griffith, who informed me that he had sent me a message with a poem that I should read.

I would expect that most every reader of this column knows who Virgil is. If you don't, suffice it to say that he's a dear friend of the community who is, in my opinion, unjustly imprisoned for speaking about blockchain technologies in North Korea a few years ago. There is not enough room in this column to do justice to Virgil's story, and if there is anything that Virgil needs more of right now, it's justice.

A brilliant and kind individual who genuinely wants to make the surveillance-ridden techno-cacotopia in which we find ourselves a better place, I count myself to be among the very lucky to have a professional relationship with Virgil that has also become a deep and lasting friendship.

Back to the poem.

I believe in poetry and the power of words. I studied both philosophy and English literature as an undergraduate. In law school, my legal writing professor used to say that all lawyers should read poetry because it teaches you how to pack a great deal of meaning into very few words. And, before lurching into mind-numbing discussions about topics such as generation-skipping transfer taxes or the rule against perpetuities, my property law professor used to start each class with a poem.

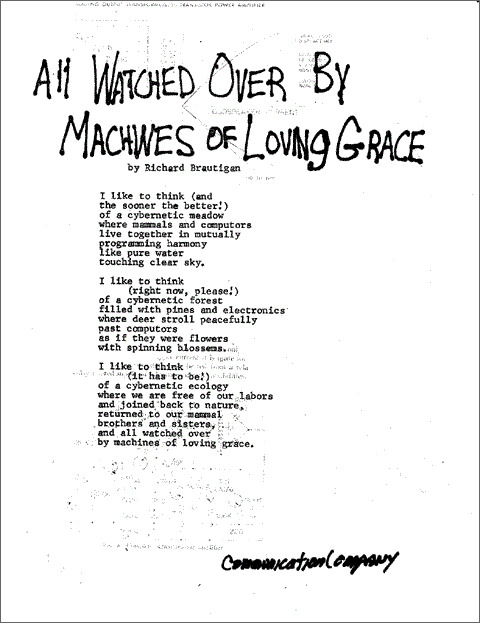

So, when Virgil recommended the poem, "All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace," I took notice.

The poem, written by Richard Brautigan in 1967, is reprinted in its entirety below:

I like to think (and

the sooner the better!)

of a cybernetic meadow

where mammals and computors

live together in mutually

programming harmony

like pure water

touching clear sky.

I like to think

(right now, please!)

of a cybernetic forest

filled with pines and electronics

where deer stroll peacefully

past computors

as if they were flowers

with spinning blossoms.

I like to think

(it has to be!)

of a cybernetic ecology

where we are free of our labors

and joined back to nature,

returned to our mammal

brothers and sisters,

and all watched over

by machines of loving grace.

|

Those words struck me instantly and viscerally. And they did with others too.

We received a great deal of positive reactions to the discussion during Off The Hook, and for several days thereafter.

One listener informed us that he was taken aback when we mentioned this poem because it has always been dear to him and that Adam Curtis, an eccentric British filmmaker, created a documentary named after the poem. An Adam Curtis fan myself, I was surprised I hadn't heard of it.

That same night I watched the documentary in which Curtis, in his unique way nearly 13 years ago, made the case that technology has not liberated humanity, but rather dumbed us down in many ways, and has permitted us to hold more simplified views of the world.

I think there is merit and demerit to Curtis' position on technology and this poem, and thus worth in considering Brautigan's words both in their totality and stanza by stanza.

What strikes one first about this poem is its prescience.

Indeed, this is exactly what Virgil first addressed with me. Written in 1967, the language throughout is perceptive and prophetic in ways that perhaps only a technologist could envision. While Brautigan was known as a Beat poet, from 1966 to 1967, he was the poet-in-residence at the California Institute of Technology a.k.a. Caltech. Coincidentally, this is also the same Caltech from which Virgil himself received a Ph.D. in Neuroscience and Computational Neuroscience.

Another aspect of the poem that struck me was that it sounds and reads almost as if an AI itself generated the content. You could easily imagine someone giving ChatGPT a prompt to draft a poem about nature and animals living in peace with cybernetic machines, and the output being very similar.

From the first stanza, we can learn a significant amount about Brautigan's vision. There's a sense of urgency: Brautigan believes that it would be "the sooner the better" for the "cybernetic meadow" he conceives to exist. Used in all three stanzas, Brautigan was rather fond of the term "cybernetic."

Of note, this term predates the poem by nearly 20 years. Norbert Wiener, a mathematician, first used "cybernetics" (a Latinization of the Greek word "kybernetes" for one who steers or guides) in 1948 in his book of the same name, referring not to the fusion of man and machine, but to a control and communication theory applicable to both animals and machines.

In 1968, nearly the same time as publication of the poem, Margaret Mead posited that the function of cybernetics was to establish "cross-disciplinary thought which made it possible for members of many disciplines to communicate with each other easily in a language which all could understand." This very notion of the harmony and oneness of man and machine is found within the description of life in the cybernetic meadow.

That is, the lives of humans and machines were seamless, like "pure water touching clear sky." Of note, the verb "live" also applies to both the mammals and the computers, by which the poem ascribes an equality of consciousness, if not biology, to both nouns.

Within the second stanza, the poem transitions from the "cybernetic meadow" to the "cybernetic forest" within which "deer stroll peacefully / past computers / as if they were flowers..."

Being laid-up in the Pocono Mountains with a broken leg, this very nearly describes my surroundings. Throughout our property, I've installed various surveillance cameras that don't just guard the property, but capture the deer as they graze and frolic in the woods and lake, and the bears as they nocturnally lumber about. Essentially web servers with a camera that exist in the wild, our deer do in fact stroll peacefully past them without any regard. Why human beings feel the need to surveil wildlife with sophisticated electronics is beyond both me and the scope of this piece.

Evolving further, within the third stanza, we are no longer in the forest but a "cybernetic ecology." It is that ecosystem of humans and machine that relieves us from the burden of labor and allows us to return to nature where, presumably with the deer, we can all stroll past computers in the wild as if they were "spinning blossoms," while being "watched over by machines of loving grace."

Aside from the value inherent to the prescience of the poem predating ChatGPT by approximately 56 years, there is a beauty in the language, vision - and especially the optimism - about the future of computation contributing to the betterment of humankind by relieving our burdens, permitting us to become human once again, and letting us live in harmony with nature.

On the other hand, the world that Brautigan envisioned, being so at odds with the world we have in fact created, is like shining a bright light on the broken promises of technology and the various ways that we have permitted computers and data to be used and abused, not to our empowerment, but to our detriment. With this backdrop, it would be fair to characterize as rather naive the idealism that Brautigan espoused with the promise of technology.

That technologically-enabled utopia - a world of great promise, harmony, and leisure - is nowhere to be found. What we have instead can veritably be classified as a technologically-enabled dystopia, where major corporations engage in widespread surveillance of human activities, and the data from that surveillance drives capitalism, which in turn creates debt, which further enslaves the human population, forcing us to continue our labors (rather than as Brautigan conceived, freeing us from them), and in many cases now, society forces humans to labor far beyond an age that would seem fair or appropriate.

There's not much harmony or grace about the world of machines in which we now find ourselves.

The exaltation of nature, as another critical example, rings as shallow. Pretty as the flowers in the meadow may be, nature is anything but peaceful and harmonious.

As Thomas Hobbes described it in Leviathan, life in the state of nature was "nasty, brutish, and short." And, knowing full well what we know now about, for example, authoritarian regimes' use of facial recognition systems to suppress populations, erode our expectations of privacy, and perpetrate human rights abuses, the welcoming of surveillance culture in the final two lines ("all watched over / by machines of loving grace") seems particularly preposterous.

On yet another hand, I truly do not think it is fair to judge Brautigan's words in the harsh light of hindsight or by the measure of the present day.

Indeed, it is hard to deny the fact that the AI-based advances in natural language processing, whether Large Language Models (LLMs) or Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPTs), are easing the burden of many mundane tasks. That unfortunately brings us back to Curtis' position that, in essence, smart machines are creating dumber humans.

That consequence aside, there is something so childlike, optimistic, and endearingly ambitious about Brautigan's poem that explains why it has captivated and inspired for so many decades.

We, as hackers and technologists, share that same child-like wonder and attitude towards ever-evolving and more powerful computers and their promise to world, and it is indeed that outlook that very much sets us apart. I submit not that it is wrong to judge Brautigan's words, but that it is too soon to do so.

Will the prophecy of his techno-utopia come true?

It may be several generations before we coexist with machines of loving grace, but whether we continue to tolerate the dystopian despair that is the current state of tech, or we plant the seeds of that harmonious, cybernetic forest is entirely up to us.

I hold out hope for the latter.