Artificial Interruption

by Alexander Urbelis (alex@urbel.is)

Concerning the Importance of Being Wrong

Readers of this column who are also listeners of Off The Hook will recall that in August I lost two family members over the course of two days to the Delta variant of China COVID-19. Though I was not terribly close to these cousins, your blood is your blood and a loss is a loss; and what makes this all the more painful is the tragic truth that both deaths were eminently avoidable - that is, if only we could more easily admit when we are wrong.

The first death was a male cousin who was 29-years-old, married, and left behind a 4-year-old daughter. The second death was the mother of the cousin who died; she likely contracted China COVID-19 from, or at the same time as, her son. My cousin died on a Monday and, because his mother's health was deteriorating, the doctors elected not to tell her that her son had died, thinking it would be such a shock to her system that it would compromise her chances of survival. That Wednesday, a few short hours after we discussed this on Off The Hook, she too died, without ever having been told her son predeceased her. I can only hope that wherever it was that they went when they left this plane, they found each other quickly.

Both lived in Florida. Both were members of an evangelical church that I believe advised against the vaccine. Both had made several social media posts about the dangers of the vaccine. Both were unvaccinated.

Since then, I have given considerable thought to the reasons why, in the face of science, data, and empirical evidence of the vaccine's efficacy, the unvaccinated insist on remaining unvaccinated. I don't claim to have a full answer, but I do think part of any explanation would have to include certain psychological idiosyncrasies arising from social media.

It is hard enough for any human being to admit even to a minor mistake, let alone being wrong about a major health-related issue like vaccination. But I believe that social media distorts the psychological calculus involved in admitting one is wrong. Putting aside for a moment the source of such disinformation, if on social media one has, e.g., shared articles musing about the dangers of the vaccine, argued with friends or family via comments or posts about the vaccine, or memorialized in some other public way that one was an anti-vaxxer, then having a change of heart about the vaccine is no longer a private, medical decision, but a matter of public record that one was wrong about this critical, life-or-death issue.

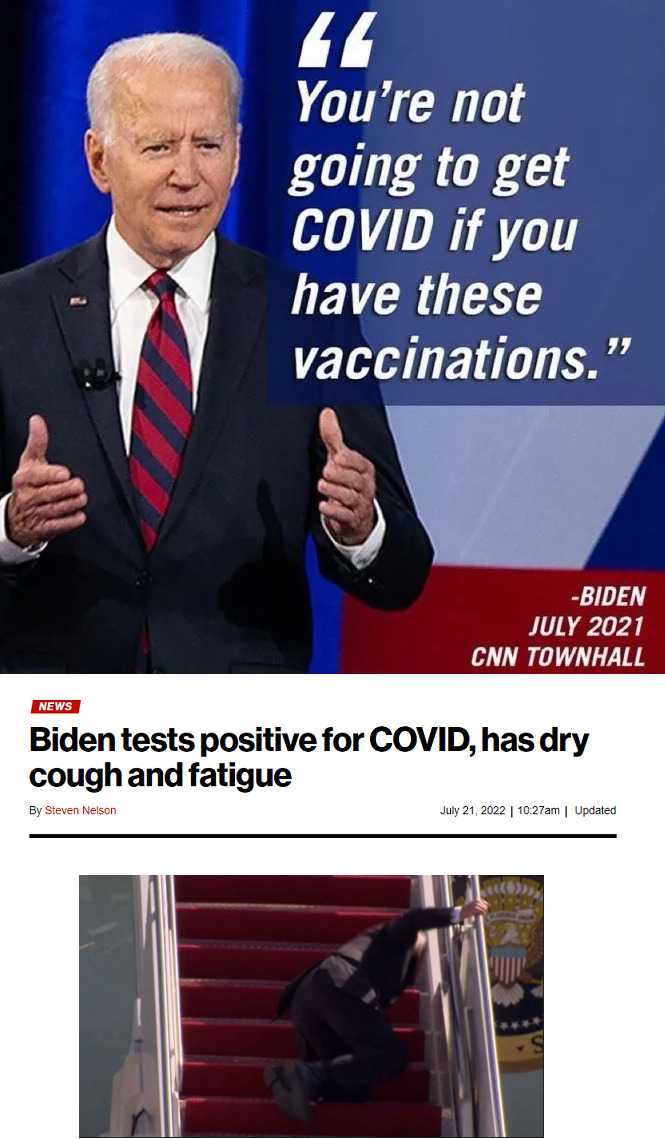

If changing one's mind about vaccination is now tantamount to a public and personal declaration of error, it is no wonder why the anti-vaxxers are so entrenched in their positions despite every effort to give them incentives, including cash, to become vaccinated. And what does not help matters is the stigma, condescension, and righteousness of the vaccinated toward the unvaccinated, be this from our friends, the media, or the well intentioned but overly paternalistic admonitions of President Biden. I'm reminded of a situation where I was once completely in the wrong, but was brave enough to admit it.

About ten years ago, a colleague was married at the U.S. Naval Academy in Maryland. It was a wonderful evening and everyone was in great spirits. I was one among many who had been over-served that night, and I woke up feeling a bit surly, dehydrated, and, to use a phrase from Kingsley Amis, it felt as if my "mouth had been used as a latrine by some small creature of the night, and then as its mausoleum." Slowly, I made my way to Baltimore to catch the train back to New York, which was readying to depart as I arrived on the platform. I'd lost track of exactly what time it was because I was arguing with my then-girlfriend about something minor which I frankly do not recall. The argument continued as I entered the train and persisted as I sat down in my aisle seat.

About a minute later, I felt a hard thump on the back of my seat, as if someone had deliberately slammed its upper half with considerable force. Still listening to the minor premises of my girlfriend's argument, I turned around, phone connected to ear, hand over mouthpiece, and with great contempt said, "Excuse me?" A man in his late 50s, balding, with glasses and a seething look in eye said to me, "This is the quiet car, you asshole, shut up or go somewhere else." Between the annoying and unnecessary argument coming in one ear and the bizarre, quasi-violent lunacy being hurled at me via my other ear, together with the fact that I'd already been suffering from a pulsating thud at the center of my skull since I awoke, my blood started to boil.

I stood, realized I had indeed sat down in the quiet car, and temporarily moved to the next car to conclude the spat with my girlfriend. At this point, my Sicilian blood was over-boiling. I approached my seat from the rear, so was also approaching my passenger-nemesis from the rear. There was no plan in my mind to do this, no malice aforethought so to speak, but as I approached his seat, I took my right hand and smacked it with near full force behind the uppermost part of his seat, causing him quite a surprise. Using that surprise to my advantage, I rather impolitely let him know that he had no right to speak to me in that manner and that if he ever did again, several swift acts of violence would fall upon him. My passenger-nemesis did not receive these threats well and our unfriendly dialogue in the quiet car persisted for another minute or two, after which I sat for a moment, then got up and went to get a coffee.

Ironically, the hot coffee seemed to cool my nerves. By the time I finished half the cup, I began to think that I acted like a child, an idiot, and a bully. Certainly, there was no reason why this man could not have been more polite, but there was also no reason for me to exacerbate the situation the way that I did. For that, I was squarely in the wrong.

I returned to my seat in the quiet car, this time approaching from the front. My passenger-nemesis and I locked eyes as I walked down the aisle. I did not sit. I remained standing and put out my hand. I said to him, "I'm sorry for the way I behaved and the things I said. That's not who I am. I'm severely hung over today, was arguing with my girlfriend, and when you hit my seat, it infuriated me, but that's no excuse. I apologize."

My hand hung there for a few seconds as he contemplated this unexpected apology, after which he said, "I'm sorry too. I shouldn't have hit your seat. I'm not myself today either." He stammered for a half second, looked down, and then said, "I just found out this morning that my wife has breast cancer."

"Holy shit, I'm sorry," I responded. I sat down and leaned around the seat so we could continue to talk. "I'm Alex." "I'm Joe." To the chagrin of the other passengers in the quiet car, we chatted the entire ride to Philadelphia where Joe departed. We never exchanged numbers or got each other's full names, but Joe and I had an unexpectedly deep human connection despite the ephemeral nature of our friendship, made possible only by empathy and apology, by admitting that I was wrong.

Had I taken to Twitter or Facebook about this situation with righteous outrage, offering an apology would have been much, much harder. I would have entrenched my position in writing, forever. And the human connection that came with changing my attitude and my position would not have been possible. This is precisely what is missing from social media exchanges, which is ironic given the major platforms' missions of building communities, bringing people together, and the sharing of ideas.

That said, I do believe there are small changes that can be made that can alter the long-term trajectory of social media for the better.

Certain colleagues and friends of mine have inexplicably been drawn to the anti-vaxxer movement and have amassed considerable followings. Amazed at this, I've studied their posts and the comments to those posts. Because I've spent time looking at these comments, mostly on Twitter, the content-feeding algorithms of Twitter now send me more and more of this dangerous misinformation. Every time I read a post about the danger of the vaccine, I think about my two cousins and the daughter that will forever be without her father.

For it is one thing to have perished in 2020 while China COVID-19 was ravishing the United States and another thing entirely to perish in late 2021 when a vaccine has been readily available in this country for most of the year. It is the difference, in a sense, between inevitability and intention. In 2021, refusal to take the vaccine is an intentional act. And while there may be legitimate health or religious concerns, those are the slim minority of reasons for refusal. Misinformation, I believe, is the reason for most refusals. And if the foreseeable consequence of misinformation (see "Artificial Interruption," Summer 2021) is the death of others, then morally, and perhaps even legally, those who spread misinformation are culpable.

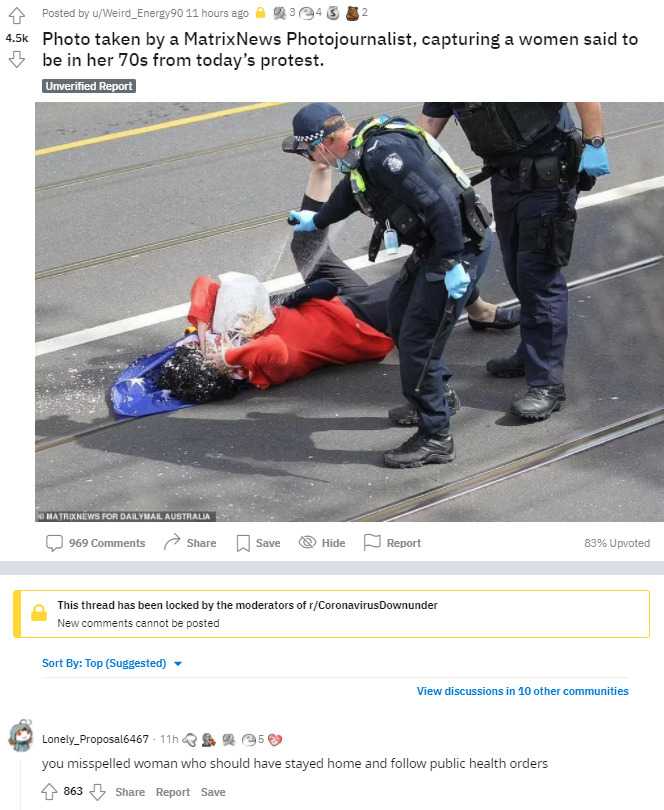

A step in the direction of liability can be seen in Australia where the High Court found that media companies can be held liable for comments on their social media pages. While this would encourage sensible moderation of a great deal of the insanity and inexplicable racism that can be found as comments to any major news story, it also encourages the kind of content moderation that would hinder the freedom of expression.

Went down to a protest,

Picked up his baton and spray with glee.

He zipped up his vest and waited for the line to break,

"You'll come a bashing some Grannies with me."

Bashing some Grannies,

Bashing some Grannies,

"You'll come a bashing some Grannies with me."

As He sprayed as He pushed as He kicked her while she was on the ground,

"You'll come a bashing some Grannies with me."

Down come some Tradies to fight the Bloody coppers,

Bashed in some Copper heads, One Two Three.

Once the Jolly Copper,

Didn't want to fight the men.

"I only signed up to bash Grannies" said he.

Bashing some Grannies,

Bashing some Grannies,

"You'll come a bashing some Grannies with me."

As He sprayed As He pushed as He kicked her while she was on the ground,

You'll come a bashing some Grannies with me.

Now Every Bloke in AUS had heard of the Jolly Cop,

His Face and Address Online for all to see.

He wasn't so tough when he wasn't Bashing Grannies,

"My days of being a shit cunt are over for me."

Up jumped the Copper and jumped off of Sydney Bridge.

"You'll never catch me alive!" said he.

And his ghost may be heard as you pass by that Harbor Bridge,

"You'll come a bashing some Grannies with me."

I believe that a more fundamental - and simple - change is needed: removing the concept of permanence from social media altogether. If building community is indeed the goal, then preserving for all eternity our divisive statements or half-baked arguments seems counterproductive. If building community is the goal, then social media users need to be given the space - and the freedom - to change their minds. An anti-vaxxer who sees the error of her ways should be allowed to change her mind without fear and without reproach. An anti-vaxxer who changes her mind should be welcomed, not stigmatized.

We should view those who change their mind and admit their faults as holding out the digital equivalent of an olive branch. Admitting fault in today's tribal culture takes tremendous courage and we should be doing everything to encourage these changes of heart. Far better than the Internet itself, the coronavirus, through its lethality, demonstrates the interconnectedness of all human beings and the present need for empathy to triumph over apathy.