What Hacking My County's Election Worker Portal Taught Me

by Keifer Chiang

Local governments' cybersecurity defenses are all that stand between us and the poisoning of our water supplies, the attacks on our 911 emergency systems, and the ransoming of our public healthcare systems. Unfortunately, many local governments are unequipped to handle such modern threats. Some such entities fail to maintain their security posture. Some such entities struggle to address found vulnerabilities. I know because I hacked my county's election worker portal.

The Hack

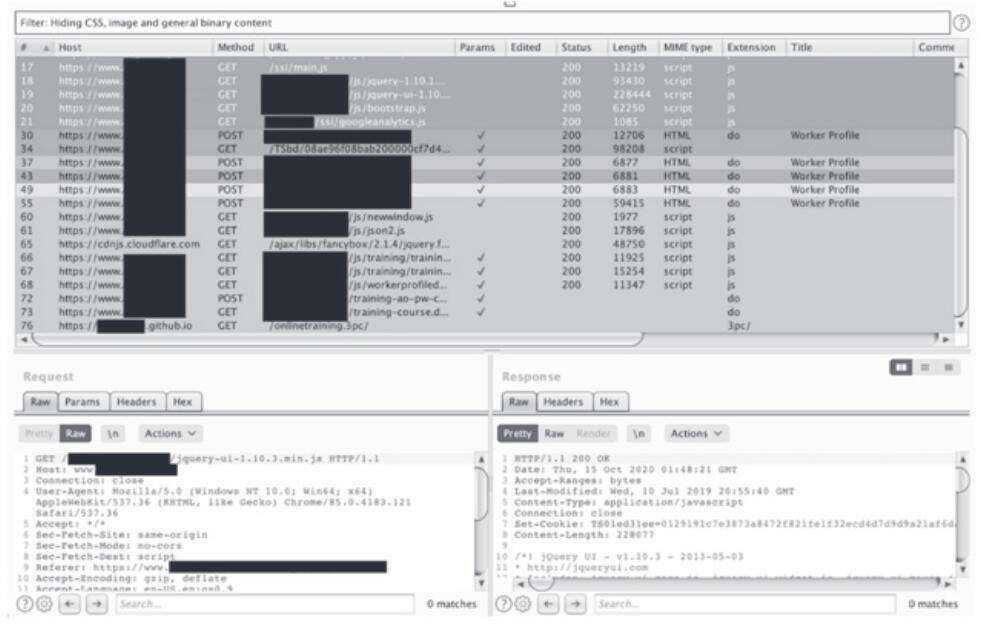

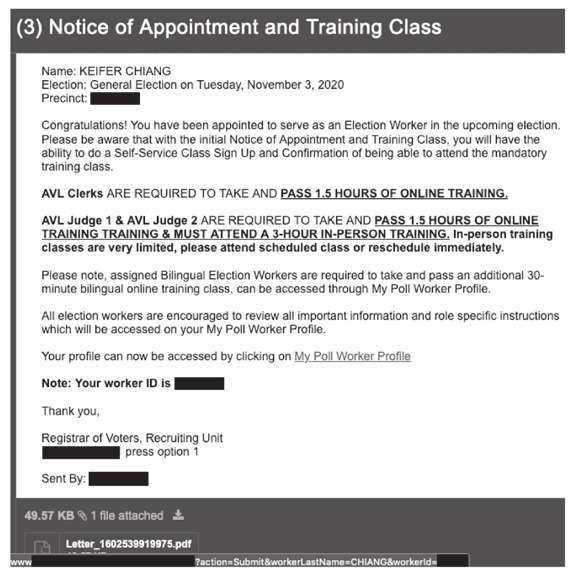

It began with an innocuous-looking email from the county's Registrar of Voters. Offering congratulations for being selected as an election worker for the upcoming 2020 General Election, the email contained instructions for next steps, a five-digit "worker ID," and a hyperlink labeled "My Poll Worker Profile." As a habit, I hovered over the hyperlink to verify the URL. I clicked. My web browser opened the election worker portal and, among the content, I found my home address, phone number, and the names and contact information of my fellow election workers. The URL had logged me in without asking for any credentials, ringing alarm bells in my head.

Registrar of Voters Email Containing a URL with a Sensitive Query String (CWE-598)

I decided to do a little digging.

Since I did not have permission to attack the portal and did not want to disrupt any part of the election system, I limited my penetration testing scope to my own account. Sparing the technical details, I found that the portal did not protect credentials (CWE-521 and CWE-598), the portal had no brute-forcing defenses (CWE-307 and CWE-308), and that external websites could potentially modify the portal's resources (CWE-15).

(The Common Weakness Enumeration [CWE] list can be accessed at cwe.mitre.org.)

Given the content in the portal, an attacker with access to an election worker's account could prevent the worker from passing a required training course, could doxx or intimidate the election worker with the available Personally Identifiable Information (PII), and could use the available information to access other election workers' accounts. Only the last name of an election worker and an unchangeable five-digit number protects the confidentiality of an election worker's PII and the election worker's availability to operate the polls.

However, this is not a story about how I hacked the county's election worker portal; it is a story about what happened after.

The Response

On October 15, 2020, after successfully conducting a proof-of-concept, I called the county's IT department for a security point-of-contact to whom I could make a responsible vulnerability disclosure. The person who answered redirected my call to the IT help desk, who redirected my call to the Registrar of Voters, who attempted to redirect my call back to the IT help desk. After I described the redirection circle, the Registrar of Voters employee informed me that they would notify the county's information security team of my request and that someone in the team would contact me.

Having received no response by October 23, 2020, I called the county's IT department for a status check. My call was redirected to the IT help desk. They directed me to send an email to the county's support desk. I complied.

Later that day, I received an email response from an information security analyst. I sent the analyst my risk assessment, replication steps, and mitigation recommendations. I also asked the analyst for information regarding the county's responsible disclosure policies and next steps.

Having received no response by the morning of October 28, 2020, I sent a follow-up email to the security analyst.

At around 6:00 p.m., I received a call from a Registrar of Voters employee who informed me that there had not been a breach in the last six years and that the Registrar of Voters was complying with all existing election laws. The employee added that the information security team was aware of my "persistence" and that the employee would "Prefer that [I] do not contact information security directly next time."

Concerned about retaliation, I did not contact the county until December. On December 9, 2020, I contacted the analyst, informing them that I would be following the standard responsible disclosure timeline and that the public disclosure of my findings would open around the end of January 2021.

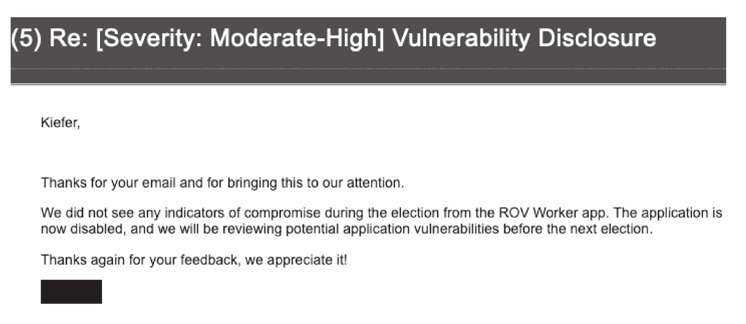

The next day, I received an email response from the analyst, informing me that the information security team did not find any indicators of compromise during the election from the portal, that they had disabled the application, and that they would be reviewing potential vulnerabilities before the next election.

December 10, 2020 Email Response from the Information Security Analyst

The Lessons

It took an embarrassingly unsophisticated attack to break into my account. I expected better from a system that affected how voting locations were staffed. We should expect better. But are our local governments realistically able to implement and maintain robust security systems when local officials may not be aware of cybersecurity needs and when local governments don't have the funds for a strong security program? A vulnerable system typically means risking users' data. A vulnerable local government system means, among others, risking constituents' drinking water and political voice.

And what happens when someone stumbles across a vulnerability? Having a vulnerability, though not ideal, is not a major cause for concern; no system is 100 percent secure. What is important is how one addresses a reported vulnerability. Therefore, reported vulnerabilities should be investigated and patched quickly and transparently. However, too often, organizations and companies are uncooperative after a responsible vulnerability disclosure, failing to respond to - or even arresting - security researchers. My attempts to get the vulnerabilities patched were largely met with redirection and silence.

It can get better. It may take local governments implementing effective employee security training programs. It may take local governments allocating funds towards building resourced security teams. It may take local governments establishing responsible vulnerability disclosure programs. It may take constituents like us providing our support and keeping local governments accountable.

Until then, someday, somewhere, another vulnerability will be found. I just hope we can handle it.