Beyond the Breach: An In-Depth Look into the Cyberinsurance Industry

by Shaikat Islam

Cyberinsurance is a portmanteau of two terms - cyber and insurance - that are often over-prescribed in our ever-interconnected world. The cult of cyber was born in the midst of the personal computer revolution that has shadowed over us since the 1970s, and the advent of the modern concept of insurance can be traced back to 1762, when a mathematician by the name of James Dodson revolutionized the concept of the insurance premium - a set amount, precisely calculated, that would act as ease of mind in case of disaster. Since then, the concept of insurance has morphed into a medley of different iterations and has become one of the most hotbed issues within the current political climate, but its essence has changed very minutely over its evolution and can be described in one word - security. In its most basic form, an insurance policy is a secure contract between one party and an insurer to protect the party against specific risks.

Cyberinsurance, also known as cyber risk insurance, is insurance designed to protect against a number of nefarious attacks and breaches on data and systems, including cybercrime and attacks such as malware, ransomware, DDoS, and botnets. The key note here is that cyberinsurance is a plan of recourse only after an incident has occurred - as a result, cyberinsurance is not an effective plan of defense.

In this new era of data-driven analytics, where the amount of data doubles every 20 months and billions are taking to mobile technology platforms to conduct their economic transactions, the triad of cybersecurity - confidentiality, integrity, and availability - are as important, and at risk, then ever. Effective measures to prevent breaches, such as data encryption, techniques such as destroy before disposal, the proper training of employees, and update procedures are only effective before a breach occurs - the question this article tries to answer is: Is cyberinsurance truly an effective measure beyond the scope of incident response and the point of return?

To the Community

Cybersecurity courses offer a great deal of information about specific measures to prevent cyber incidents, as well as detailed glimpses into proper cyber defense, but leave a great deal to be answered as to what occurs within an entity after an incident happens. It is common to see discussions of "X Breach Occurred at Y Company: Millions Affected" within course discussion pages, but one becomes curious to know exactly how organizations deal with breaches after the fact.

Cyberinsurance is one of the many recourses of action that are implemented after a breach occurs, and a popular one at that (cyber risk policies are expected to reach a $7.5 billion dollar market by the end of 2020), but much is left to be answered as to whether or not policies are as truly effective as advertised.

The Evolution of Cyberinsurance and Its Efficacy

As Internet use began to grow at a feverish pitch during the late-1990s, many commercial entities were looking to capitalize on the network, and many succeeded. Ask Jeeves, Netscape, and larger than life institutions such as Amazon all owed their success to that commercialization, but there were no effective loss control measures put in place to secure the intangible resources that made up a bulk of these Internet companies' assets. Data that made up these companies' assets, such as credit card numbers, personal user histories, and other sensitive information were susceptible to breaches and, as of 1997, there were no risk policies implemented to protect companies after a breach happened.

As it turns out, the birth of cyberinsurance owes its existence to luck. Steven Haase, then an insurer working with an insurance agency in Atlanta coincidentally found himself working with a colleague at American International Group (AIG), implementing the Internet Security Liability Policy, which was translated to other policies at ACE Insurance and Lloyds of London, an insurance company based in England. In "What Agent Who Wrote First Cyber Policy Thinks About Cyber Insurance Now" by Andrea Wells, published in Insurance Journal, Haase finds that one of the most egregious problems with cyberinsurance in its current state is the lack of education that insurance agents have when dealing with such policies. Agents, in his view, do not understand the product enough to sell it effectively, leading many to wonder how truly effective these policies can actually be.

As of 2018, there are 528 insurers based in the United States that underwrite cyberinsurance claims, which is an increase of 47 from 2017, due to a demand driven by increased awareness, and the number of claims report a 39 percent increase from 2017 to 2018. Furthermore, the top ten cyberinsurance policy writers lay claim to 69.5 percent of the market share within 2018. As can be seen, the demand for cyberinsurance skyrocketed after its humble birth in 1997, which can be linked to countless factors, the most prominent being the rise of Internet technology within business use, as well as the commodification of data.

The current cyberinsurance market comes in three manifestations: third-party written coverage, first-party written coverage, and implicit silent cyber coverage. Third-party coverage is most similar to medical malpractice insurance, where the insurer reimburses organizations for costs that occur due to cyber incidents, which is what was most similar to the type of policy underwritten by Haase. First-party written coverage is a more broad insurance policy that can be written for any company that uses technology and accounts for company specific needs, however broad or large. The third type, called implicit silent cyber coverage, is one of the most interesting as it extends coverage to Property and Casualty (P&C). Say that you buy a fire alarm with an attached webcam that rests in an unsecured port on your local network and that fire alarm is connected to your sprinkler system which sits upon your expensive collection of moisture-sensitive, limited edition, Matisse artwork. If your fire alarm were to be breached and your sprinkler system set off, theoretically, based on the coverage underwritten by your provider, your artwork would be insured.

The problem with that last case is that it is emblematic of how specific and esoteric risk analysis for writing cyberinsurance can be. Networks, databases, and systems are hard enough for sysadmins to decipher after years of on the job training. Insurance agents, as Haase mentions earlier, cannot be expected to fully understand all the minutiae that goes behind designing a cyber risk policy in tandem with the complexity of computer networks and systems.

Furthermore, cyberinsurance is not as effective as auto insurance or health insurance when it comes to history. There is a large, recorded database of different accidents, loss calculations, and settlements that can back an auto insurance policy; for cyberinsurance policies, this history is not nearly as broad (due to its birth in 1997) and complexity inundates cyber risk analysis. What is probably most egregious in the cyberinsurance market is the possibility of a wide scale cyberattack, as well as the short incubation periods of malware. A large scale attack on a single point of failure such as Amazon Web Services, which is utilized by hundreds of thousands of small and large entities, could possibly lead to claims for hundreds of thousands of claimants, which would be impossible to fulfill by the cyberinsurers. Car accidents, diseases, and property damage can all be quantified in terms of a ceiling and floor function for risk, but how does an actuarial scientist quantify the risk for malware that constantly changes every two days, or new instances of ransomware and constantly changing cyber incidents?

Cyberinsurance is not as concrete as insurance companies claim. There is a plethora of unknown knowledge that can influence the state of a breach or cyber incident, and many cases of company-sponsored insurance negligence, like the one described for Mondelez below, are emblematic of the uncertainty that faces the cyber risk market.

Case Study: Mondelez

In 2017, ransomware (which is malware that is designed to deny access to crucial system functions until a ransom is paid) was in vogue throughout the world. WannaCry, attributed to the Lazarus Group, was demanding payments in Bitcoin and left many crucial systems such as those in hospitals and government offices in paralysis. Recently after, NotPetya, another type of ransomware, resulted in one of the most devastating cyberattacks in history: Merck, a pharmaceutical company, lost $870 million. FedEx lost $400 million. Many other companies and government agencies lay in paralysis as NotPetya, whose purpose seemed to be to destroy disk structures and wipe data, spread itself across computer networks with worm-like features, using the EternalBlue and EternalRomance SMBv1 exploits.

One of the companies affected was Mondelez, a confectionery and snack company responsible for Cadbury, Oreo, and Toblerone. They lost about $100 million dollars over computer damage and distribution disruptions, which, according to their insurer, Zurich American Insurance, was not covered under their plan.

The reason?

Zurich American Insurance denied Mondelez' claim on the basis that it showed traits emblematic of a warlike, or hostile, actor, which was not covered in their policy. Simply put, Zurich American Insurance believed a nation-state actor was responsible for the attack, and denied coverage for Mondelez because their policy does not include that coverage. The problem with this exclusion lies in the insurer's claims. Zurich American Insurance's claim that a warlike actor had perpetrated the incident was unprecedented until that point, and was unproven at that point, until February 2018, when a group of NATO nations attributed the malware to Russia. The question now is, can Mondelez' claim be denied based on information that was not freely available retroactively, and how do cyber risk providers divide the line between nation state actors and individual actors when it comes to the origin of an incident or exploit?

The Mondelez vs. Zurich case has heavily influenced discussions of the cyberinsurance industry and its efficacy, and has proven that the industry is still in its infant stage of development. The fact of the matter remains that the current consensus within the industry is that cyberinsurance providers simply do not have access to the large datasets employed by other risk analysis entities, and until such a dataset is employed for the calculation of cyber risk, cyberinsurance is simply not effective at what it aims to do - provide security, ex post facto.

Case Study: The City of Baltimore

This case, like Mondelez', also began with ransomware - this time, by the name "RobbinHood." In May of 2019, a majority of the City of Baltimore's servers were shut down, leading to $18 million in damage. The malware was distributed through hacked remote desktop services and other Trojans, which made the malware a more individually targeted incident. Once a computer was affected, all personal data became encrypted until a payment, made in Bitcoin, was provided.

Just recently, the City of Baltimore made headlines by purchasing a $20 million dollar cyberinsurance policy between Chubb Insurance and Axa XL Insurance, two of the leading cyber risk providers. In detail, the City of Baltimore paid $500,103 for $10 million in coverage from Chubb Insurance, and $355,000 for $10 million in coverage from Axa XL Insurance. According to the Board of Estimates and the Comptroller of Baltimore, the coverage includes: cyber incident response coverage (including an investigative team); business interruption loss and extra expense; contingent business interruption and extra expense loss; digital data recovery; network extortion; and third-party coverage for cyber privacy, network security, payment card loss, regulatory proceedings, and electronic social and printed liability.

While the breadth of definition for this policy is limited by the public documents provided by the City of Baltimore, the description of the policy is as general as can be. There are no provisions for the definition of a cyber incident actor, nor are there provisions for the limitation of coverage for specific attacks, which, using the case of Mondelez, would prove to be very valuable to have. In "Baltimore Bought $20M in Cyberinsurance. Such Policies are Becoming More Common" by Stephen Babcock, Jeff Bathurst, a security consultant, provides a quote that has become ever too common in the cyber security industry - "Insurance companies are working to come up with more accurate models, while companies are still figuring out how much cyberinsurance coverage they need."

In short, it can be inferred from the above that the coverage purchased by the City of Baltimore, while effective in some cases that are distinctly defined in the policy terms, is still in infant stages, and is less effective than it was marketed to be.

A Sentiment Analysis on Top Cyberinsurer Companies Landing Pages to Determine Link Between Subjectivity and Polarity

A mature market for cyberinsurance has yet to emerge for a number of reasons, including lack of actuarial data, accounting difficulties, and a lack of legislature regulating the industry. But one interesting reason that Tridib Bandyopadhyay, Vijay Mookerjee, and Ram C. Rao posit within their paper "A Model to Analyze the Unfulfilled Promise of Cyber Insurance: The Impact of Secondary Loss" is that companies may be afraid of revealing that they have undergone a breach to their insurer for fear of ruining their reputation in the public sphere.

Previous sections have discussed bad faith on the part of the insurers, specifically Zurich American Insurance, a company that disputed a claim over unprecedented reasons, and also have mentioned bad faith on the part of insurance agents, who, according to Haase, lack the proper knowledge to truly understand the product they are selling.

As a result, I believed it would be interesting to perform a sentiment analysis on the landing pages of the ten major cyberinsurance firms, which includes Chubb, Axa XL, AIG, Travelers, Beazley, Farmers, Zurichna, Progressive, Arbella, and Allianz. Considering the lack of faith of many experts within the current state of the art of the industry, I thought that a sentiment analysis on the landing pages of these firms would resemble a scenario in which an entity in crisis were searching for cyberinsurance as a means of security. As for my methodology, I scraped the readable text-data from each of the landing pages, preprocessed them for Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) tasks by removing punctuation, lower-casing input, as well as removing any conjunctions and stopwords (words that provide no value to the semantic of a sentence, such as articles).

After doing this for each of ten websites, I converted each text block into a word list, which was matched against an opinion word list provided by Minqing Hu and Bing Liu as part of an appendix for their paper, "Mining and Summarizing Customer Reviews," published at UIC. After finding the positive, negative, and neutral proportion values for each of the web pages, I created word clouds for each web page, and then ran a sentiment/polarity assessment on each web page using TextBlob, a pre-trained NLP package for Python.

Insurer Negative Rate Positive Rate Neutral Rate AIG 0.10677966101694915 0.061016949152542375 0.8322033898305085 ALLIANZ 0.10137795275590551 0.0344488188976378 0.8641732283464567 ARBELLA 0.10462287104622871 0.024330900243309004 0.8710462287104623 AX AXL 0.0776255707762557 0.028538812785388126 0.8938356164383562 BEAZELEY 0.10874200426439233 0.06823027718550106 0.8531645569620253 CHUBB 0.06638566912539515 0.03371970495258166 0.8998946259220232 FARMERS 0.11392405063291139 0.03291139240506329 0.8531645569620253 TRAVELERS 0.07776669990029911 0.03389830508474576 0.8883349950149552 PROGRESSIVE 0.11505681818181818 0.029829545454545456 0.8551136363636364 ZURICHNA 0.10272536687631027 0.033542976939203356 0.8637316561844863 |

Figure 1: Negative, positive, and neutral sentiment rates for each of the top ten cyberinsurance provider landing pages.

In Figure 1, which describes the sentiment analysis results using the opinion word list, AIG had the largest proportion of positive opinion words, while Arbella had the least positive opinion words, showing the largest percentage of negative sentiment.

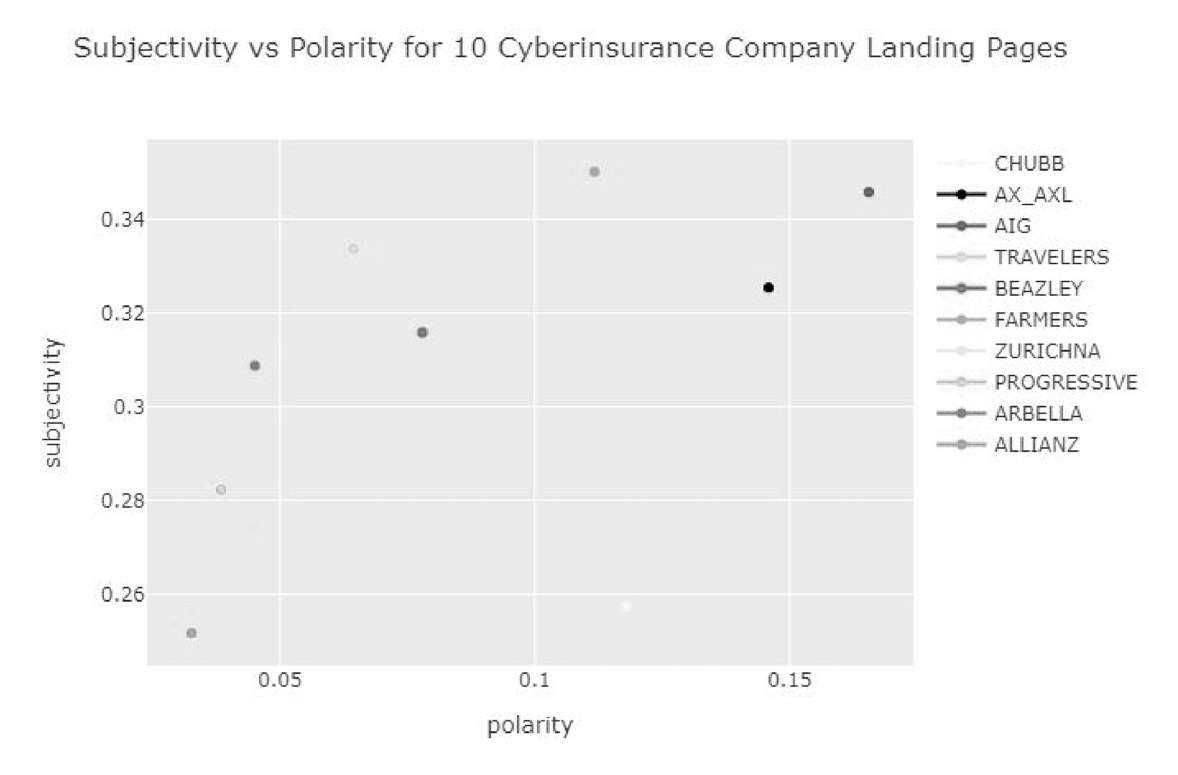

Figure 2: Subjectivity and polarity scores measured using TextBlob for each of the ten cyberinsurance providers' landing pages.

Interestingly enough, in Figure 2, which describes the subjectivity vs. polarity for the ten cyberinsurance company landing pages, AIG also had the largest polarity as well as subjectivity, suggesting that the language used on their website is most subjective. Allianz had the least subjective and least polarizing language of all ten companies. Ranges for polarity were from 0.0326 to 0.1655, and ranges for subjectivity were from 0.2517 to 0.3457.

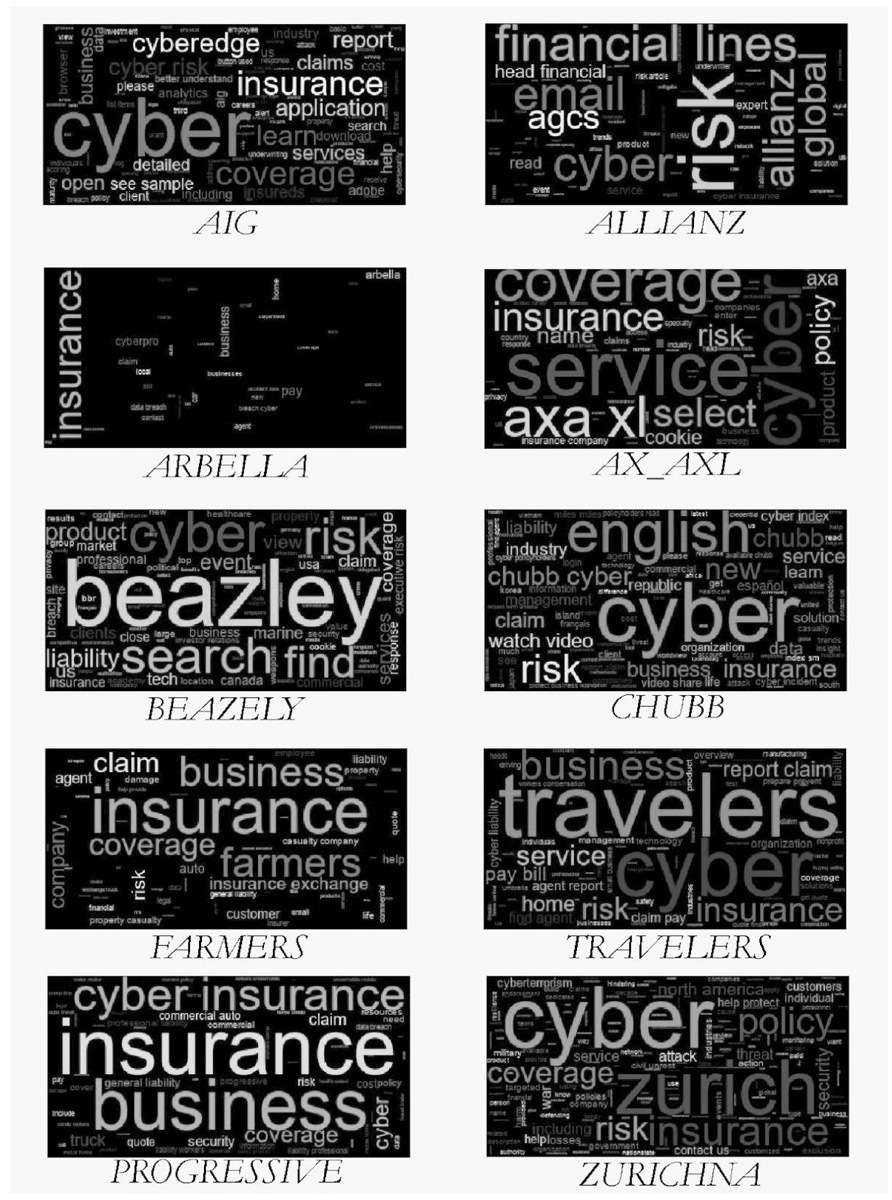

Figure 3: Word clouds describing the frequency of words, as they appear on each of the top ten cyberinsurance providers' landing pages.

These results can correlate to the word maps for both companies, which can be seen in Figure 3. AIG's word cloud has notable examples of buzzwords, such as "cyberedge," while Allianz's word cloud seemingly lacks any such vernacular, instead including such neutral terms as "financial," "risk," and "underwriter."

From these results, one can only suggest that individuals or entities looking for cyberinsurance coverage should take companies' advertisements with a grain of salt. In 2016, insurance markets capitalized on 1.27 trillion dollars of premiums, which allowed them to spend so heavily on marketing and advertising. The insurance space is one of the most heavily advertised industries in the United States and the world, so much so that each large industry company has its own mascot - think the GEICO Gecko, the GEICO Cavemen, Flo from Progressive, Aflac, and the "We Are Farmers" jingle. Anyone looking for insurance should be knowledgeable about what they are buying beforehand, perhaps with the aid of a third-party consultant.

Action Items and Suggestions for the Cyberinsurance Industry

The cyberinsurance industry began with the advent of the consumer technology revolution and suffered from growing pains as it struggled to match the efficacy, literature, and history that provided other forms of personal loss insurance industries their great market success. Today, there are hundreds of insurance companies that provide some sort of cyber risk liability, but do so with many uncertainties - there are no regulatory agencies for insurance companies to determine whether or not cyber incidents are acts of nation-state actor aggression or individual attacks, which led to Mondelez losing hundreds of millions of dollars which they were seemingly insured for.

Furthermore, insurance companies currently do not have the ability to provide coverage for the increasingly large and mutating body of cyber incidents and malware that continuously changes and plagues the cyber space each year. If a cyber attack was insidiously crafted to destroy an electrical grid, or shut down an ISP or a cloud hosting company, the ramifications would be disastrous for both the industries affected directly by the attack, as well as the insurers, who would have to cover the billions (possibly trillions) of dollars in claims.

As a result, it is my suggestion that the current industry double down on the scope of their policies. Ensure that the client has an understanding of what exactly they have coverage for and whether or not that applies to malware that may have been spread by a foreign entity, perhaps by agreeing to have that claim be validated by a neutral, regulatory, third-party expert.

Furthermore, cyberinsurance companies should do their best to ensure that the way they analyze risk is least subjective as possible. Efforts to do this could be propelled by the creation of internal, thorough databases of cyber incidents and loss. In continuation, cyberinsurance companies must also ensure that their employees are knowledgeable about the terms of their policies as well. It is unacceptable that insurers can sell a product that even they might not know the entire ramifications of.

Finally, cyberinsurance companies must orient their policies to change. Cyber incidents are not the same as they were a year ago, let alone a decade. By defining the scope of their policies to the largely evolving and growing space of cyber incidents, cyberinsurance companies can guarantee the efficacy of their policies. And, as a word to the consumers, one recommends that they ensure they have a full understanding of the scope of their coverage, perhaps by consulting a cybersecurity expert who is a neutral third-party, in order to prevent millions of dollars in "uncovered" claims as in "Case Study: Mondelez."