Artificial Interruption

by Alexander Urbelis (alex@urbel.is)

All Things that "Suck" May Not Suck

In the first installation of this ongoing column, we abruptly halted just as I was lamenting the scarcity of legitimate gripe sites these days. This lamentation, readers will recall, was sparked by my harrowing experience trying to replace a broken iPhone with T-Mobile in the midst of the pandemic, during which T-Mobile initially refused to cancel an order, insisting I return to a T-Mobile store, inside a mall, to perform this unarguably simple task.

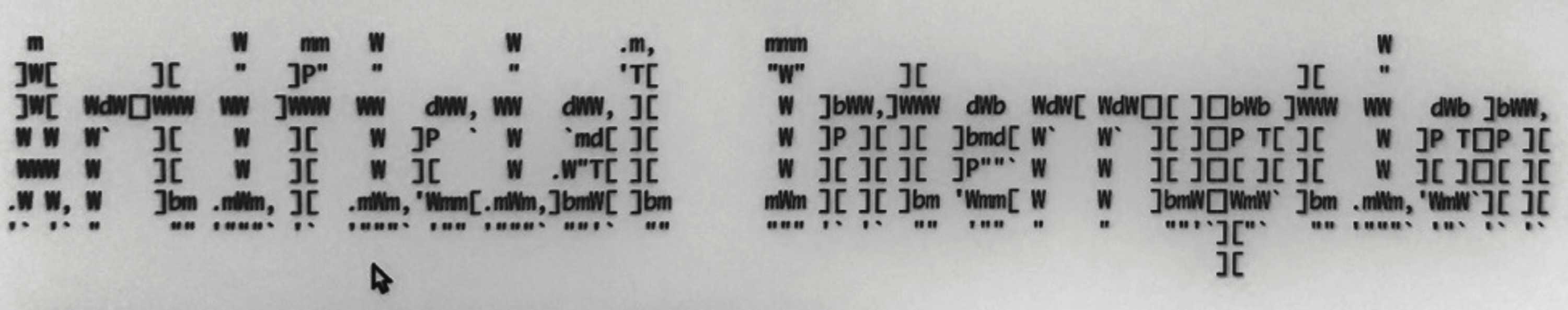

Using the DNS intelligence platform I built, I identified ten domain names that contained both the strings "tmobile" and "sucks". I then examined the NS records of each of these domains using a script I wrote to perform a dig ns $domain +short, format the output, and hunt for NS records based on a string I specified. (As an aside, examining NS records of a domain can be as useful in determining ownership as WHOIS records; and if you're interested in looking up tens of thousands of NS records, unlike WHOIS lookups, there are no concerns about being rate-limited.) The output of that script is below:

From this small data set, we can make some lamentable deductions.

First, the fact that there are only ten domains that focus on a major telecommunications provider sucking is a clear signal that the days of gripe sites may be long gone.

Second, as the NS records indicate, the host of two domains is MarkMonitor. MarkMonitor is a well-known and often-used corporate domain name registrar. And the two most valuable gripe site properties, i.e., tmobilesucks.com and tmobiletvsucks.com, have NS records indicating that T-Mobile itself owns these domains. What is more, upon further examination, T-Mobile also appears to own tmobile-sucks.com. Curiously, both tmobile-sucks.us and tmobilesucks.us are the eldest of all the domains, dating from 2002, and both of these are hosted in Germany.

Third, and critically, not a single one of these ten domain names resolves to anything substantive at all. This was surprising and depressing. I'd thought that at least one of these would resolve to a landing page with a few words about a horrible customer experience or perhaps even an anachronistic "Under Construction" sign placed there a decade or two ago by an energized and pissed-off customer, who then simply never got around to putting that gripe site together because life and work and family and hobbies and something - anything at all - got in the way. Dejection set in. Gripe sites were a perennial thorn in the side of every major corporation and every major service since the 1990s. Moreover, corporate criticism being a form of speech and expression critical to the legal doctrine of fair use, the existence of gripe sites was, in essence, a bulwark against the constriction of the doctrine of fair use. And the doctrine of fair use, especially in the context of the Internet, was a cornerstone of the freedom of expression. In a sense, fair use is that which prevents intellectual property rights from infringing on the Bill of Rights.

Perhaps we are past the days of the gripe site having any relevance. Have the SEO magicians in combination with Google Ads relegated gripe sites to the oblivion of the third or fourth page of search results? But couldn't social media platforms amplify and spread the word about the existence of such outlets even if they were to be found beyond the event horizon of the first page of search engine results? Unfortunately, since outrage appears to be one of the major components of the fuel which powers most social media platforms, sustained outrage would be necessary to propel continued traffic to the site. Given that most social media platforms neither permit nor amplify repetitive or similar posts, this would likely fail.

To this, some would say, "Who cares?" If a customer is unhappy, received subpar service, or was ripped off, there are plenty of other avenues available to give life to such complaints. Yelp and Google reviews are the two platforms that come to mind and have the most influence and impact on a business. But these are insufficient, precisely because they do not specifically focus on the customer who has been wronged. In this sense, the balanced nature of allowing both positive and negative reviews dilutes the force of the gripe. Sure, they may give a voice to the aggrieved patron of your local taco joint who wants to vent about there being too much (or too little) cilantro in the guacamole or the horror of having to wait for 15 whole minutes for a round of mojitos, but these complaints pale in comparison to the nature of the wrongs that one would often see on websites dedicated to the seriously aggrieved.

And more to the point, Yelp and Google and every other major platform do not permit anonymous grievances to be aired. E.g., to write a Yelp review, one needs to register a Yelp account associated with verified contact details including an email address, and then the poster has to be logged into the platform with that account not only to post a review but also to even read others' reviews. What this means is that the platforms are tracking your likes and dislikes, they're tracking the devices you use, they're tracking your IP address, they're tracking the comments you leave and assessing your relative education level, and they're combining this data with third-party data, packaging it up, putting a creepy bow on it, and using all of this data to drive ad sales. What is more, the platforms are very likely sharing or selling this data to affiliate organizations as a little kicker to enhance profit margins.

A separate major distinction and deficiency of relying on platforms like Yelp or Google is that they only permit reviews - good, bad, or otherwise - of local businesses, not nationwide or worldwide corporations. You may be able to really rip into that idiotic waiter at your local Italian joint who brought you a Sangiovese instead of the Valpolicella that you ordered, but there's no mechanism for you to air your objectively accurate opinion that pizza from the nationwide franchise of Papa John's is absolutely horrible regardless of whether you ordered it in Dayton, Ohio or Missoula, Montana. Similarly, I can rip into my local T-Mobile shop, but any review I would like to make about T-Mobile generally as a company operating across the United States and many places in Europe is impossible. This prevents one's voice from having the force and effect of a grievance that would have been found on a gripe site in the days of old.

If I were to guess, this limitation is by design. It would not be technologically infeasible to allow reviews of major corporations through a single platform or app. But doing so would allow users to criticize the very companies that could be advertisers or might be interested in user data. So, to permit this would be potentially cutting off a fertile source of income. And how can we forget about legal liability? Your local Italian joint is unlikely to have the resources to stifle negative commentary by filing lawsuits for defamation, trademark infringement, brand dilution, etc., but your average larger national or multinational corporation certainly is.

This dialectic drove me to the powerful conclusion that the age of the gripe site should not be past, and that there is still a place for these domains and websites that may seem like digital anachronisms in the age of there being an app for everything. As hackers often do, I went a few steps farther down the rabbit hole.

I started with the new .sucks Top-Level Domain (TLD). In 2014, ICANN approved .sucks as a new TLD and it was delegated into the root zone of the DNS in February 2015, meaning that was when the TLD went live. From the outset, however, brand owners objected to this TLD because it was seen as potentially extortionate: all major brands would be expected to make defensive domain registrations to prevent the domains from falling into the hands of someone who could actually do something meaningful with it, and the registration fees always hovered around $2,000 per domain or more for premium domains! Because of this absurdly high price barrier, a .sucks domain is economically infeasible for ordinary people to acquire. That said, as of the time of writing this article, there exists 11,483 domains in the .sucks zone file, the vast majority of which are registered and owned by corporations themselves.

Going farther afield and farther down the rabbit hole, I began monitoring daily domain registrations for anything that included the string "sucks." The results were both a reflection of the psyche of the planet and fascinating on other levels. Cooped up, quarantined, and socially distant, it was not a shock to find whytheworldsucks.info registered on 26 October. And given the RIAA's recent DMCA takedowns of youtube-dl on GitHub, on 31 October, we found riaasucks.com, which came as a shock only because the domain was actually available.

And it also occurred to me that - like the T-Mobile examples above - because corporations anticipate that their services are going to suck, they are often the very entities that register "sucks" domains in the first instance. This means that if, perhaps, in the investment context, one were interested in generating something like alpha based on the plans of major service providers or companies to roll out a new product, one could monitor the DNS for domains associated with MarkMonitor or CSC (another corporate registrar) which also contain the term "suck." These hits could all relate to hitherto unannounced corporate plans.

Putting aside exploiting "sucks" domains for profit for a moment, another somewhat nefarious thought crossed my mind. Much the same way that threat actors utilize the subdomains on top of generic-sounding domains to launch sophisticated cyberattacks, what if the same methodology were re-purposed to provide a centralized platform for corporate grievances. For instance, if a platform for criticism were hosted on top of a generic domain, every company could be a separate subdomain such as tmobile.genericdomain.com or amazon.genericdomain.com.

The legal import of this is fascinating from an IP perspective as well. ICANN forces domain name registrars to abide by the terms of the Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP) that permits brand owners to initiate an abbreviated arbitration proceeding to reclaim domains registered by cybersquatters. I use this UDRP system regularly to reclaim malicious domains and sure-up clients' cybersecurity posture in the DNS. But there is no legal authority for any sort of abbreviated arbitration or legal proceeding that applies to subdomains. In fact, subdomains are deliberately outside of the jurisdiction of the UDRP. And if the domain on which the subdomain was hosted was entirely generic, no corporation subject to criticism would have the legal standing to attempt to transfer or cancel the domain.

Interestingly, the same law that has allowed giant platforms like Facebook, Google, Snapchat, etc., to flourish without fear of legal retribution for the content of data that flows through their networks - Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act - would give our hypothetical gripe platform the same immunity.

What if we created this platform and it was run by the hacker community, and its existence ensured by lawyers willing to defend to it? Isn't this exactly what Section 230 of the CDA was meant to protect? More on this endeavor in the months ahead. Until then, stay safe, stay sane, and stay masked.