A Carrier Pigeon Revisited

by David Savage Lightman

I read Joseph B. Zekany's article "Decoding a Carrier Pigeon" in the Summer 2015 (32:2, page 31) issue and as an U.S. Army school trained cryptologist (MOS 98B), I decided to respond.

While I give Mr. Zekany kudos for trying to decode it, he is way, way off.

Not only was I a cryptologist with the Army, I spent most of my time as a Special Forces soldier and encoded/sent a huge number of operational messages using one-time pads and Morse code.

Without a doubt, the message was encoded using a one-time pad.

It is unbreakable without the one-time pad key. Here's why:

1.) While this message was sent by a pigeon, it could also have been transmitted by radio using Morse code. Note that the first group is the same as the last group - AOAKN.

This is the first group on the one-time pad used to encode the message. Without knowing which one-time pad was used, the base (receiving) station would never know which one-time pad to use to decipher the message. AOAKN is repeated at the end to ensure that the base station knows which decrypt pad to use in case the first part of the message is garbled. Having a five-letter group repeat in 27 groups is extremely unusual - unless it's the pad identifier. Any military cryptographer would notice this right off the bat.

2.) The number 27 at the message end represents the group count of the message. A group count is used to ensure that the entire message is received. The message has 27 five-letter groups. That's why Sgt. Stot wrote 27 at the end. It's kinda like a check digit.

3.) The numbers 1525/6 are the one-time pad page serial numbers that were used to encode the message. All one-time pad pages have unique serial numbers. The serial numbers are used for accountability. Should a one-time pad be found, it can be traced back to the soldier who lost it. One-time pads are classified crypto material and to lose one is a very serious infraction.

Sgt. Stot was also helping the base station operator find the one-time pad page quickly by putting the serial numbers on the message. Otherwise, the operator would have to look through a huge stack of one-time pads to find the page that starts with AOAKN. Finding a page by serial number is much faster. The base stations are receiving literally hundreds of messages every day and anything that can help them speed up the process is appreciated.

Most one-time pads used by forward military units have 20 or 25 groups per page.

They are designed to fit in a soldier's pocket. Let's assume that Sgt. Stot's pads had 25 groups. He would have to have used two pad pages to encode his message. Ditto for 20 groups per page.

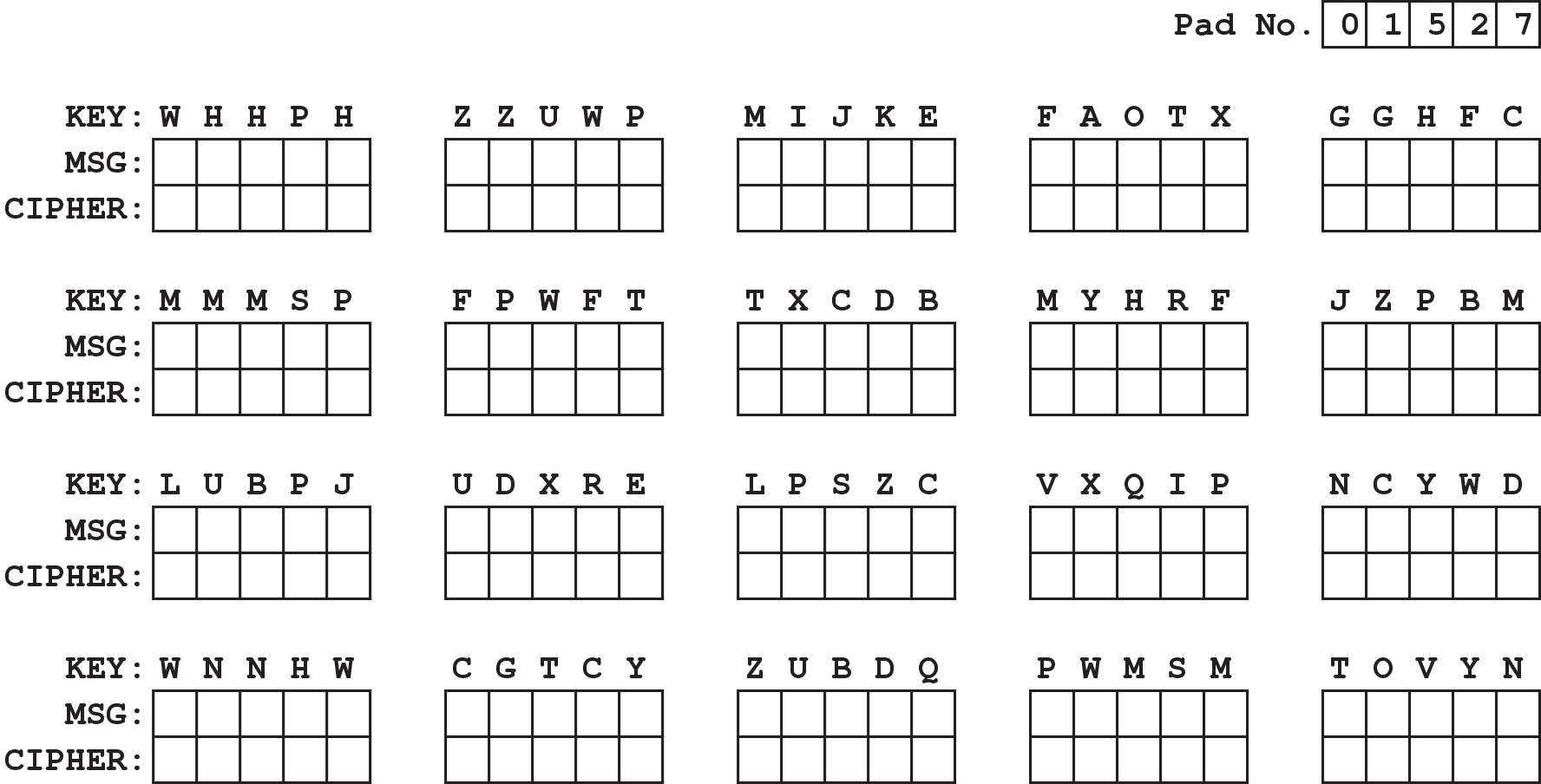

So you can deduce that Sgt. Stot used two pages to encode the message and those two pages were page numbers 1525 and 1526. (See the graphic that shows a typical OTP sheet for field use.)

4.) I agree that the "NURP 40 TX 194" and "NURP 37 OK 76" are pigeon numbers. All enemy information would be encoded, especially map coordinates. No enemy intelligence would be sent in the clear. They are not grids and certainly do not reference "Tiger Wehrmacht." British & U.S. land maps do, in fact, use grids. Depending on the map scale, they would most likely use eight-digit grids i.e., "TR12345678." On a 1:50,000 map, that is within ten square meters.

Note that at the bottom of the message, the number "2" is written in the box for "number of copies sent." This means that two birds were flown to ensure that the message got through. Thus, the two bird numbers.

5.) The message was written at 15:22 (3:22). Sgt. Stot filed his copy at 16:25 (4:25). Got to love the Brits sticking to procedure!

6.) This is a short message. It's only 25 groups of content (the first and last groups are pad identifiers), so they are using brevity codes. In the U.S. Army, we used what is called a Standard Audiovisual Services Supplement (SAVSERSUP) that lists standard messages and code words for common items. A report code name is sent along with data for pre-defined paragraphs. The messages become much shorter than if everything is written out. Even if you could break the message, without the code book it is impossible to understand what is being sent.

Plain Text Example:

Broken Out:

The above solution is a CLOUD report that I just made up data for and shoved into 27 groups to show you what a decrypted message would look like. As you can see, the plain text isn't a lot of help without the code book. The XXXX is a filler to fill up the last group.

7.) Since I don't have the decrypt pad or the code book, and neither does Mr. Zekany, there is no way to ascertain just what the message contents are. Mr. Zekany's plain text analysis pure speculation and isn't supported by any cryptanalysis theory or practical methodology.

8.) The bigger question is why did the Brits use carrier pigeons in the first place? Why not use a radio? The answer is simple. Bandwidth. During World War Two, just about all ground radios used crystals to select a frequency (channel). Since crystals were expensive and heavy to carry, there were limited numbers of frequencies to use and the demand outstripped the number of frequencies available. Variable Frequency Oscillators (VFO) were not very rugged, light, or accurate in the early 1940s and crystals ensured the forward unit was on the same frequency as the base station. Getting an assigned frequency took a lot of work by a Signal Officer. Instead of fighting for a radio channel, a unit could employ pigeons and not have to worry about a radio.