Transmissions

Running a Hostile Network

by Dragorn

The network at HOPE (were you there? If not, what's your excuse?) presents an interesting set of challenges.

It's both physically difficult, because the hotel lacks any significant infrastructure, and technically difficult, because a hacker con is rarely the most gentle of environments. Weird hardware, bored people causing problems, and sheer population density all create some interesting issues.

Physical infrastructure at the Hotel Pennsylvania is significantly limited. While we're fortunate enough to have a wired network which covers most of the Pavillion floor (Floor 2), there isn't much else for a tech conference to take advantage of, which leaves us the challenge of building it all from scratch the day before the conference.

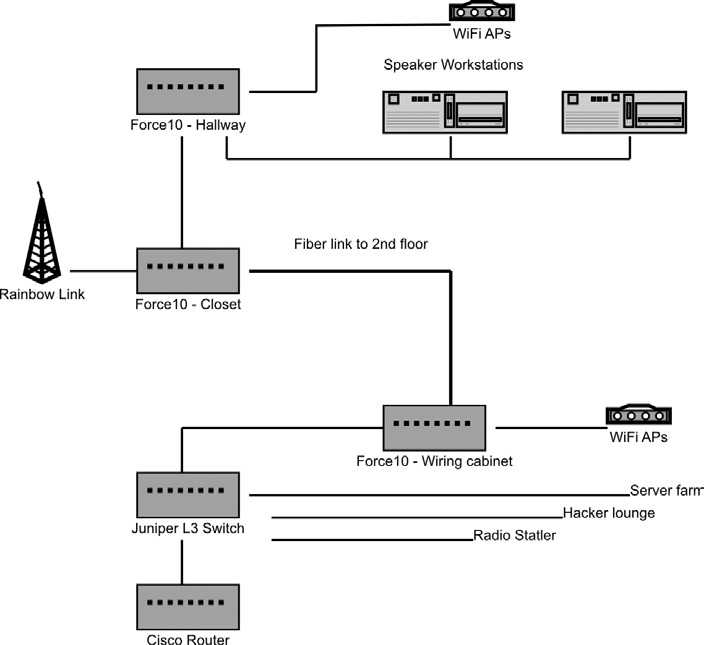

The HOPE network typically consists of about 1000 feet of fiber optic cable, 5000 feet of Cat 5, and two dozen wireless APs. The exactly layout varies year to year depending on what gear is contributed. For HOPE Number 9, the core network was assembled from HPE Aruba, Cisco, Juniper, and Force10 gear.

The biggest challenge comes from the wireless network.

Because wireless is the primary method of giving network access at the con, pretty much everyone who is going to use the network at HOPE (which, to be fair, is far from everyone) is going to be on the wireless. In addition to the wireless network, various areas such as the Hacker Lounge provide wired access. Most of the wired access and project space is on the Pavilion floor.

Wireless is, of course, susceptible to denial-of-service attacks. Wi-Fi has its fair share to be sure and, even if there weren't denial-of-service vulnerabilities at the 802.11 layer, it would be trivial to saturate the spectrum with noise. Fortunately, it seems like most of the people who were entertained by this have gotten over the novelty, and generally deliberate denial-of-service attacks are fairly rare.

Unfortunately, Wi-Fi is shared media, meaning accidental denial-of-service attacks happen all on their own, when 500 people in one room fire up their connections at once. The best way to avoid congestion is to move users to other channels. By tuning the access points to try to move people to 5 GHz, anyone with a dual-band card should have found themselves on the higher spectrum with more channels free than we could use. However, most smartphones and tablets lack 5 GHz support, which gives us no way to get them off the super-congested lower channels.

In 2.4 GHz, there are only three non-overlapping channels available (1, 6, 11). If access points are too close to each other, then even those channels may overlap. The network control software figures out how to keep adjacent APs from overlapping, but in an area like the conference room where the main talks are held, all clients will be overlapping each other, causing collisions constantly. Collisions in turn cause packets to be re-sent, which cause more packets in the air, which cause more collisions. It gets ugly, fast.

To try to mitigate the disaster in the 2.4 GHz spectrum, there are a few options (and we tried them all). They have various levels of disruption on the network. What works for one conference may not work for others, or may not work the next year, depending on what users want to use the network for. Outright breaking the network for some modes of operation can keep it functioning for the rest of the con.

You can tune the APs to be lower power, so each access point covers less floor space (in theory). When the room is a single large, open room, this won't help much, plus clients will still be shouting at full power, saturating the channels. Access points can be set to drop broadcast packets and multicast packets. This helps (a little) reduce the total packet count on the channel, at the risk of breaking some video streams and other multicast actions.

Additionally, limiting the number of users allowed on each access point can increase effective speed. Even though each access point covers most of the conference floor, clients tend to stick to the first one they've seen.

By reducing the number of connections allowed on each AP, clients are encouraged to connect to different access points - hopefully the closest one, with the strongest signal. With sufficient coverage from access points, there's no reason to allow more than 30 or 40 clients per AP. Limiting the signal level threshold also limits the number of clients connecting to an access point. Preventing clients on the other side of the room from connecting can, in theory, reduce interference.

All of these methods introduce minor instabilities into the network. By forcing clients to roam to a new access point, when they otherwise might not, definitely can introduce latency or connection resets, and blocking traffic such as multicast and broadcast can prevent some tools from functioning (such as Apple mDNS auto device discovery).

In the grand scheme, however, these limitations allow the network to function at a usable level, when previously it could not. Before implementing these tweaks, the HOPE network saw about 200 to 300 simultaneous users. After enabling them, that number jumped immediately to 300 to 500. The spectrum was so crowded, hundreds of devices couldn't actually establish a usable connection.

Thanks to a generous donation by Net Access of IP space, there were enough Internet-addressable IPs to be able to give them out via DHCP. This meant there was no NAT and no firewalls on the HOPE network this year. This had the double benefit of reducing the load on the network gear (NAT and firewall takes a fair bit of power), making it easier to get cheaper gear to run the network, and it supports the ideals of the conference - the fewer barriers between an attendee and the Internet, the better.

It always pays to remember the environment when deploying a network in a particularly unusual or hostile area, and to also remember the intended use and the reasonable expectations of performance. These decisions would never be necessary on a home network, because they would never be necessary with a handful of devices.

For a corporate network, the impact of forcing users to roam more often might not be seen as acceptable, but the range of devices would also be more tightly controlled, allowing for smarter device configuration and capabilities. For a conference, I'm willing to bet being able to get online consistently is the most important attribute, and without mitigation factors, there wouldn't have been much of a network.