Transmissions

The Great Firewall of... Dot-com?

by Dragorn

A government institution determines that a website contains unacceptable material, and blocks access to it from within that country.

Smells like censorship, but for the sake of argument, let's (briefly) say that controlling what is acceptable is the government's job, and not just for Big Red. Australia does it, and "first-world" countries around the world are working on doing it.

Now consider: A government institution determines that a website contains unacceptable material, and blocks access to it from the Internet at large by hijacking the DNS records. But even this, maybe, has an explanation. Obviously a government ultimately controls what is considered valid within its assigned domain name space. Libya is welcome to enforce whatever standards of conduct it feels like, holding domain shortener vb.ly in violation of Islamic law by shortening URLs that may contain offensive material.

But what if the domain was a dot-com address, one of the great three top-level domain trees, registered outside of the nation in question, and was seized without notification by an organization chartered with defending the nation against underwear bombers?

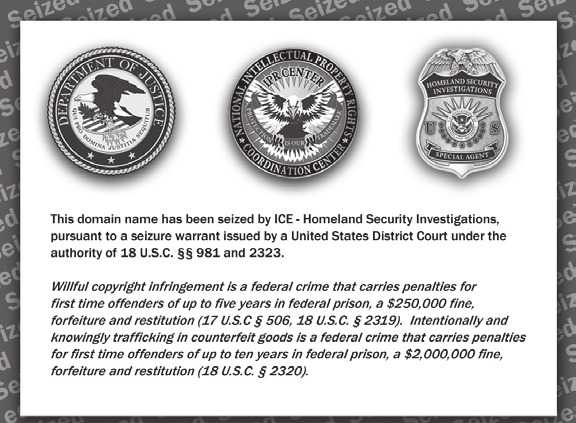

That's right; the Department of Homeland Security, or more specifically, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the people responsible for policing the borders, or (from the ICE website) "ICE's primary mission is to promote homeland security and public safety through the criminal and civil enforcement of federal laws governing border control, customs, trade, and immigration," apparently now has the power to override registrations in the dot-com (and one might assume other top-level DNS) trees hosted in the United States.

The ICE is responsible, among other things, for preventing the import of counterfeit goods. In a recent takedown of 75 domains, the ICE shut down what would appear to be 71 websites hawking counterfeit handbags, golf equipment, and sports jerseys - and four sites about sharing links to rap music and torrents.

And, of course, it gets even better: The torrent site doesn't even run a tracker, and doesn't host torrent files. It's a torrent search aggregator, which loads results in an <iframe>. It's not even scraping results. The only action it's taking is replicating a <form> POST action.

We're not just looking at the slippery slope, we're tobogganing down it trying to dodge pine trees and plastic Santa decorations. With no prior notification, the ICE is taking down websites which arguably do not fall under its jurisdiction, and which do not contain infringing material, or even, arguably, links to infringing material.

Of course, it is still a site which most people would label a bad citizen, reducing public outcry and complaints, truly the best of all slippery slopes.

Assuming that the website distributed copyrighted material (it didn't) or encouraged it by linking it (it doesn't), it may fall under the purview of the ICE under some odd interpretation of "import" or "counterfeit," but really it just feels like the MPAA has their hands in Uncle Sam's pockets again. The whole thing seems even more suspect in light of Senate Bill S.3804, the Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act.

The COICA would call for redirecting DNS records, banning ad services, and preventing any financial transactions (i.e., credit card payments) originating from U.S. addresses, to any site the government declares supports piracy (literally, "No demonstrable, commercially significant purpose other than sharing copyrighted files").

The COICA does not provide any obligation for killing the domain name records outside of the United States, but for domains registered under ICANN (i.e., dot-com), it would seem unlikely that they'd be allowed to persist.

Domains squashed by ICE have been redirected worldwide, regardless of the legalities of the site in the owner's or operator's home country, and, bizarrely, regardless of where the server is located: As of the time of writing, torrent-finder.info still functions, and resolves to a server hosted in Texas. The seizure affected the DNS entry only, not the actual server, despite the server (apparently) being located within the jurisdiction of the United States.

So far, the COICA has passed unanimously through the Senate Judiciary Committee, however, at least one senator has pledged to block the bill through the end of the current session, after which the new senate takes over. But if the ICE has the ability to blacklist sites worldwide, why do we even need the COICA?

The problem is not that the ICE isn't acting within its charter. Let's say that it is, at least, for the context of websites selling counterfeit products. The problem is that the ICE is also targeting websites which technically have no infringing aspects, and there is no (or at least, none that I could find) publicly known method for redressing mistakes, recovering domains, or even pleading the case in court to present the other side of the argument. Armed with an indisputable court order, the ICE can, in theory, seize any website in dot-com, no matter where in the world it is registered or hosted.

The ICE is able to enact these restrictions on the top-level domains because the U.S. still retains sole control of ICANN, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers.

The ICANN is responsible for defining the top-level domains worldwide, dispensing IP address blocks, and controlling the main root DNS servers. ICANN is a relatively new organization (1998) and takes direction from public meetings held around the world, but is still fundamentally a United States construction: It retains ties to the U.S. government, and operates from within the United States.

The top-level domains like dot-com and dot-net are handled entirely by U.S.-based corporations (Verisign).

In 2009, the European Union repeated a call for ICANN to cut ties with the U.S. government, and become an international entity under control of the G-12 (the twelve most economically powerful countries). This doesn't seem like much of a solution, either. What better way to paralyze the Internet at large than submitting it to the control of representatives of a dozen countries, with different laws and different interpretations of copyright.

Unfortunately, there doesn't seem to be much of a solution: Leave control of the core Internet services under one country, subject to the whims of that government in the name of "preventing piracy," or give control to a dozen competing nations and hope they fight each other enough to prevent any significant harm from being done.

Or, of course, they could all adopt ACTA, the secret closed-door trade agreement with just about every poorly planned reactionary policy about Internet use, and we'll all be screwed.

The real questions at the end of the day are: When will the United States exercise this top-level kill against websites again, what recourse do international (or even domestic) site operators have, and how can we prevent "stopping piracy" from turning further into "stopping any technology which might have dual-use?"

We've already lost unencrypted cable and unencrypted video and audio between components, forcing independent technologies like TiVo to license with specific providers and leaving customers of some providers with no choice at all.

We've already lost streaming video between arbitrary devices and, if the content providers behind the "stopping piracy" bandwagon have their way, we'll lose the ability to play one copy of a video on multiple devices - because obviously, playing it on a TV and a laptop means we should buy it twice, right?

Blocking content is censorship, and once it becomes easy for a government to censor some content, it becomes easier to censor more and more content.

Wax up the skis, make some hot chocolate, and get ready to dodge some pine trees. The slippery slope awaits.