Fiction: Message of the Day

by Peter Wrenshall

I enjoy reading your magazine, and though I am not a computer hacker or cracker, I thought you might be interested to hear about how I once nearly got arrested for hacking and ended up working as a security consultant.

It happened while I was clerking for one of the big haulage firms. The job involved tracing delivery trucks, photocopying documents, and delivering mail, even though this was twenty years after the experts announced the arrival of the paperless office. It was hassle from nine to five. From the first day, I wanted to quit, but having left school two years earlier at sixteen, I didn't exactly have many career choices. I was studying at night school to become a computer network engineer, but I was three exams away from being qualified.

The only good thing about the job was that I was free to wander around the entire building with the mail cart. Within a few days of starting, I had found a deserted part of the building, the east wing of the sixth floor, where I could go and slack off, and look down at all the rat racers running to and from their interesting, high-paying jobs. Even better, I could get some coursework done.

On the Friday of my first week, I hid a pile of study notes under a stack of mail and rolled the mail cart up to the sixth floor. I walked past the sign showing what the spiffy conference suite they were building up there would look like when it was finished, and I went into one of the empty offices. I opened my notes, and started reading about IP version six. I hadn't been studying long when I noticed a persistent tapping sound. I looked around, but there was nothing in the room, which was bare. There wasn't even any carpet. I went out into the corridor and peered into the office next door. On the concrete floor, almost hidden from view, was an ancient computer workstation, which looked like it had been built not long after the dinosaurs had died out. I could see that error messages had filled the screen.

"It's none of my business," I thought. But as I say, in those days I was fixed on the idea of working with computers, and it wasn't long before my curiosity got the better of me. I went into the office, and crouched down to take a look. There was a manufacturer's decal on the front of the machine but nothing else. I looked around for some tag or label to tell me what machine it was and, more to the point, what it was doing alone in a deserted room, but the machine was as bare as the room it was in.

A network cable came out of the back and went into a socket on the wall, so I figured that the computer was still in use as part of someone's not-quite-dead project, or that it had simply been forgotten about. The noisy hard disk whirred, died, and then whirred again, as if the machine was doing some work in the background, or had become stuck in the infinite-loop that 1960s science fiction foretold. I looked at the screen filled with error messages. Whatever program had been running, it had well and truly fallen over, since the command-line was available, leaving the machine totally open.

The cursor blinked at me, as if to say, "Please help me, for I am broken."

I've always liked computers, and they've always liked me, so I was happy to reboot this machine to allow it to continue the labors the ancients had set for it. But first I thought I'd have a little look, you know, just to see what operating system it was running.

Bending low to type on the keyboard, I opened a few files and soon found out the machine was running an old version of Linux. I was just considering whether I should open the password file, to add my own user account, when I heard the voice of doom behind me.

"What are you doing?" it demanded.

I typed the exit command and hit Enter. After the screen had cleared, I turned to see some guy in his forties, wearing overalls.

"Nothing," I said, weakly. I went to leave, but he was a hefty guy, and he blocked the doorway. "Wait there," he said. He pulled out a mobile phone and dialed.

"Hello?" he growled into the handset. To cut a long story short, the room soon filled with people, most of them wearing suits that would have taken a quarter of my yearly salary to buy. The only one to introduce himself was Barker. He was, he said, the IT manager.

"Who are you, and what were you doing with that computer?" he said.

"I'm Karl Ripley. I noticed the machine had crashed," I replied, avoiding any reference to my being a mail clerk on my first week.

"Tampering with computers is an offense."

"Criminal offense," added the admin, just in time for the arriving security guard to hear it. There was a lull in the cross-questioning while everybody seemed to be waiting for me to say something. A couple of Microsoft minutes went by, but I couldn't find anything to say. My brain was slowly filling with images of me pushing a mail cart around the Cedar Creek Federal Correctional Facility. I wondered what kind of jail time does hacking carried.

"I wasn't tampering, just looking. I know I should have phoned the help desk, but it's my first week here, and I forgot the number." Actually, I had never known it. The only computing that general clerks were allowed to do was computing the square root of nothing.

"This kid could have been hacking," the admin said. "I think we should call the police." My stomach did a somersault. Obviously, this crufty-looking workstation held some sort of commercial data, like the payroll details for the last ten years or the file on who won Office Clerk of the Month. I looked around at the crowd. Nobody objected to the admin's suggestion. I saw the security guard move slightly to his left, blocking the exit a little more, and I felt the first drop of sweat run down my forehead. Only Barker looked unconcerned.

"Let's not overreact," he said. "Somebody walks into an open office and looks at a computer, it's hardly a felony."

"This area is closed off," the admin said defensively. "Nobody is allowed up here."

Barker turned back to me, and said, "What are you doing in this section, anyway?"

"I push my cart through here," I said, a bit breathlessly. "It's shorter than going back through the other section twice."

It all sounded innocent enough, which in a way it was. Barker let out a weary breath.

"I don't have time for this," he said to no one in particular. He looked at me, and then looked at the machine, then back at me again.

"You didn't do anything with that machine?"

"No, definitely not. I was just looking."

"Yes, but I don't get why would you be interested in it, anyway. What business is it of yours?"

I shrugged. "I wondered what had gone wrong with it. The screen was full of errors." I stopped talking, hoping that it was explanation enough. When that didn't get any response from Barker, I continued.

"I'm taking a night-school course in computers, and there's a troubleshooting module. I thought that I might recognize the errors."

Barker looked around at the suits, to see how they took my explanation. Then he looked me over, and I realized that he just wanted to get rid of me. Like most IT managers, he probably had twelve hours of work to fit into an eight-hour workday.

"Look," he said, "I'm going to give you the benefit of the doubt this time, because it's your first week here, and you obviously don't know the local rules. But from now on, this section is off-limits. And if you see any problems with any other computers, then do us all a favor and just ring the help desk. Don't stand looking at the screen, because around here..."

I felt the tension in my body vanish, and I was just about to start breathing again when the guy in overalls, the one who had found me, interrupted Barker.

"I told you, he wasn't just looking at the screen," he said. "He was typing on the keys." I'd forgotten he was there. The whole room turned to look at him, and Barker glared at him, as if he was annoyed at him for making a big deal out of nothing. The janitor glared back. Maybe, I thought, he also used the sixth floor for slacking off or brewing moonshine or something, and I had intruded on his turf.

"I saw him," he added defensively. Barker turned back to me. His eyebrows rose as he waited for an answer. There was no sense denying it.

"I only cleared the screen," I said. "I was going to call it in to the help desk when I got back downstairs." That was lame, and I cringed while saying it. Barker looked more disappointed than annoyed.

"Can you check what he typed on that machine?" he asked the admin.

"Possibly," was the admin's reply. He sounded unsure. That was a good sign. In my experience, it's rare to find an administrator who is as good with Linux as he is with Microsoft Windows. It's like finding someone who can write with their left and right hands equally well. Most people I knew used either Windows or Linux. I was hoping the admin standing at the workstation fell into the Windows category.

"I'll check the history log," he said. My hope of him not knowing Linux vanished, and my heart sank. The history log on Linux is the file that keeps track of every command typed, and I knew that it would have a list of my recent activity. As I say, I am not much of a hacker, and hadn't bothered to delete anything to cover my tracks. I hadn't expected there was going to be an investigation. Thank god I hadn't created a user account. "Hacker creates backdoor to steal commercial secrets," the headlines would have said.

The admin logged on to the machine, and I watched him open the history file for the root user.

"He's been looking in the process directory," he said. He looked up with an outraged expression like a TV lawyer, only less sincere.

"What does that mean?" snapped Barker.

"He was probably trying to find out what services are available." Barker turned back to me, assuming the full authority of his official role.

"Did you type those commands?" he demanded, jabbing his finger at the screen.

Until then, I had wanted to be honest, and if it had been just Barker on his own, I'd have told him what I had done. Even though what I'd done wasn't itself a crime, I knew that someone somewhere could probably make a three-act courtroom drama out of it. They'd lawyer up and hang me out to dry, I knew it. So I lied.

"Which commands?" I said innocently. The admin helpfully stepped away from being in front of the screen, and I made a pretense of looking at the evidence. There on the screen were the commands I had used to inspect the machine. But I soon realized that in his eagerness to prove his point, the admin had made a mistake. Not only was he not a Linux guru, he wasn't much of an admin, either.

"No," I said, firmly. "That just tells you what the last commands were. It doesn't tell you who typed them, or when they were typed. It could have been anybody. And it could have been weeks ago."

I thought I saw a hint of a smile appear on Barker's face, which was quickly replaced with his official expression. I had impressed the suits, too. A few raised expectant eyebrows toward the admin. There is a surprising lack of bias in management stiffs. Sure, they obviously enjoy a good feeding frenzy, but you'd think they'd automatically cheer for the guy in the most expensive suit, and that's not true. Instead, it's a case of line 'em up and may the best man win.

Barker stood there silently, looking at me, perhaps wondering if what I had said made sense. I wasn't sure myself. My Linux skills were not exactly brilliant, but I was hoping that they were better the admin-from-hell's.

"Who are you?" Barker said suddenly. Then he rephrased it. "I mean, you don't work in my department. What is it you do here?"

"I work in the mail room," I croaked, which had an even better effect on the suits than the history-file remark. Barker looked around, clearly puzzled. The admin looked at me, and I knew he knew he couldn't back up his accusation. I also knew that I'd made an enemy forever. Office enemies, though, I can live with.

"You can't let him go," the admin said. "Those commands must have come from him."

"You don't have any evidence," said Barker.

"He was seen typing by a witness. It is a criminal offense to access a computer that you are not authorized to use. If you don't call the police, I will." He unclipped a mobile phone from his belt. He was going to use it. I had another vision, one of my career being over. Not only that, but these people were from one of the biggest companies in the country. They didn't deal in dimes; they were used to working with millions of dollars daily. When asked to assess the damages to their supposedly-hacked network, they'd have no trouble cooking up some seven-figure sum to put in front of a judge. I got a hollow feeling in my stomach. I knew that even if I didn't get jailed, I'd have a hacking rap on my record, and then nobody was ever going to hire me to work in computers ever again. I was going to be a fifty-year-old general clerk, still living with my parents, hoping to have a heart attack just so I didn't have to push that cart around an office I hated.

We stood in silence for a moment, the admin poised to dial. I could see the security guard tensing his hands, getting ready for action. In the silence, I heard the machine's noisy hard disk spin up again, and start whirring, and I looked at the screen. And then I had my second brain wave of the morning.

"It's not a criminal offense," I said. "Not on that computer."

I waited for Barker to say something, but nobody said a word. I pointed at the screen, where the admin had just logged in.

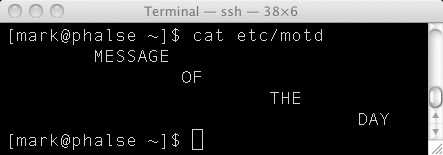

"Your system says 'welcome' whenever anybody logs in."

Every head in the room turned to look at the screen. There at the top was the message of the day, the text that accompanies every logon. Right next to the name of the company was the word "Welcome."

"A welcome can be legally construed as an invitation. Plus there was no warning that this is a restricted system."

I watched my audience, their business brains digesting the information.

"And, since the program had crashed, and I hadn't actually logged in," I added, "then legally speaking I haven't done anything wrong." Barker turned to the admin.

"Is that true?" he asked. The admin stood there, holding his phone, and tensing his jaw. He didn't reply. Actually, I had no idea if it was true, either. Barker let out a long breath through his nose, then spoke again.

"How many other machines have we got like that?" He wasn't holding back now. He was seriously annoyed, and he was letting the admin have it. Luckily for me, there was some administrative turf-war going on between the two. Office politics: don't you just love it?

"I don't know," said the admin, reluctantly. "You'll have to ask Bill. It's his box." I gathered that Bill was the company's UNIX wizard. "But this kid shouldn't be touching it."

"It shouldn't be on the floor in an empty office. What's it doing in here anyway?" snapped Barker. The admin was going to say something, but Barker preempted him.

"You'd better get Bill up here today. I don't care what he's doing; tell him to get up here now. We need the standard warning message on every Linux machine, today."

"But there are dozens of them," said the admin, a bit whiny.

"It's simple. Just change the message of the day," I suggested helpfully.

Barker shot me a look, and I shut my mouth, and looked suitably serious. Contrite, I think is the word.

"Just get it done," he said to the admin. "And get this machine out of here and into the server room."

The admin was outranked, and he knew it. He nodded silently. At the back of every office drone's mind is the mortgage he has to pay. More likely, the admin was simply following the route to the top that the ads secretly suggest: obey silently, and one day you can be the winner of the rat race. Barker turned to me.

"Go back to your work, and if you touch another machine in here, I'll personally call the police."

"I won't," I said. "Thanks."

I headed to the door. The guard stepped aside to let me pass, and I left him and the Inquisition to their post-event discussion and went out. I grabbed the cart and hustled along the corridor as fast as my wheels would go. I hit the button to fetch the elevator, and I could hear the suits filing out of the room, their spectator sport over with, going back to writing memorandums to the board. The door opened and I got in. As the elevator descended, I said a silent prayer to whomever the patron saint of hackers is, and quietly resolved that my first-born male child would be named Barker.

I exited on the ground floor, almost colliding with one of the junior clerks who was always bugging me about putting her mail on the desk instead of in the proper tray.

"Oops," I said, with a friendly smile. She was cute, and I guess the recent excitement had caught me off guard, the adrenaline had given me confidence, or something, and so I said, "How's it going?" or words to that effect. She walked away without saying anything, the perfect end to a perfect day.

I went down the corridor and into the mail room, and I stayed there until five o'clock. It's funny how a close brush with imprisonment can make mail sorting seem like fun.

I never found out what was on that workstation or why it was in that empty room, and I never asked. But I did get a call on the following Monday. It was Barker. He wanted to know if I would like to work for him in the IT department. He said that needed someone with Linux skills. Of course, I accepted, and a few months of study and three exams later, I was given the official title of network engineer. Basically, I get paid to play with networks, to see where the security holes are, and occasionally to swap out a broken switch.

These days, I can afford to buy computer equipment from this century. I never went back to a life of criminal hacking, and I've never had to push a cart around an office ever again - so far. But I did manage to bump into that clerk, the one I collided with on my first week. This time, I got a smile, and as I watched her walk away, I noticed a bit of a sway in her hips that hadn't been there before.

I'd tell you about how the computer on her desk developed a network fault that only I could fix, but you can probably guess the details.