Hacker Perspective: Phillip Torrone

by Phillip Torrone (fill@2600.com)

What's hacking? I suppose the definition that's always the easiest to explain - or start conversations with - is someone who looks at the things everyone else sees, but in a new and different way that's not immediately apparent. Sometimes this lens focuses on a cause, a project, or the desire to fight for people who can't necessarily help themselves. It's part curiosity and it's part sharing. But most of all it's human nature. It's hard to stop millions of years of evolution. We're meant to take things apart and figure out how they work. Sometimes these activities aren't immediately understood or they're considered criminal by some. But over and over again history has proven endless tinkering yields some of the best results.

I spend my days and nights writing how-tos on building electronics, publishing print and electronic information in an effort to reclaim part of the heritage of the country I'm a citizen of, the United States of America. We are a nation of hackers and tinkerers. Ben Franklin wasn't a president, yet he resides on the top denomination of our currency. That's how important the inventive is. You can see my work in the pages of MAKE Magazine, Popular Science, hardware hacking books, and lots of techie sites around the web. I think the "how-to" is one of the most powerful things anyone can create. It can change minds and influence politics. It all depends on what you're sharing...

On display at the Computer History Museum (computerhistory.org) is a Blue Box previously owned by Steve Wozniak, co-founder of Apple Computer. Why in the world would a piece of subversive technology made to get free phone calls be celebrated alongside Cray supercomputers? It's not the device that's so special, it's the subculture it created, which still represents what hacking and exploring technology is all about for a lot of past, present, and future hackers.

I'm here to tell you we're approaching a new age of hardware hacking that will have profound consequences on the decades ahead. Look around your home - dozens of cheap devices assembled in other parts of the world, brought to you at the lowest possible price.

It's cheaper to buy something assembled than to get individual parts. Over the last ten years as the prices of gadgets and doodads dropped dramatically (you can get a digital camera for under $10 now), the ability to get information out has greatly increased on an individual level.

Flawed as they are, wikis, blogs, RSS, YouTube, etc. simply do not care about secrets or nondisclosure agreements. The information on how things are made and how to bend them is getting out there. The "recipes" of how things are made, their individual components, and their secrets aren't as mysterious as they once were.

Want to make that "single use" camera multi-use? Or use it as a night vision cam? No problem. A hardware hack and firmware mod later you have a cheap reusable device for just about anything (tinyurl.com/y6k3z8).

Part of this "movement" of sorts is "open-source hardware," or open design.

To quickly define this: open-source software has and will continue to have a huge impact around the world - unpaid, loosely connected legions of developers have more strength and usually outperform any counterpart in the proprietary software arena. People who work on hardware see the same benefits possible and are bringing these practices to the world of the physical. Engineers to garage tinkerers are putting hardware under the same licenses you see with computer applications.

This isn't anything new.

Ask you grandparents about their AM radios they lovingly built, maintained, and repaired. It would be unheard of to not have user serviceable parts or documentation. Recently we almost lost our way with extended warranties, tamperproof devices, and sealed hardware. It became cheaper to toss that old PDA than to repair. But now hit Google and see the hundreds of projects, parts procurements, and possibilities with that old hardware.

Companies and even governments don't exactly like people taking things apart or circumventing "protections" and here is where the subversive part comes in. Subversive usually (means "a systematic attempt to overthrow or undermine a government or political system by persons working secretly from within." Not exactly the perfect definition. After all, there aren't any secrets. It's out in the open. But even the simple act of tinkering with electronics or unlocking your cell phone is certainly working within the system to enact change.

It starts out with simple acts of rebellion; anyone can buy a CD, rip the MP3s, and play their music on any device. Why in the world can't you do that with a DVD? Companies make portable video devices and expect us all to go out and repurchase content we already own to watch it on the small screen. That's not acceptable, so what happens? Dozens of open-source applications are shared and posted to rip the DVDs. This isn't piracy. The people who pirate things will always get around any protection. This is just fair use.

If you buy a cell phone and want to switch carriers (GSM), the carrier unfortunately "locks" the hardware and you'll need to purchase a new phone. Of course, the crafty individual will quickly see there are dongles, codes, and articles on hardware unlocking. It's such a common practice, everyone looks the other way.

These examples have gone on and on for years.

Finally, in November of 2006, there was change. The Library of Congress approved a few copyright exemptions. Professors can legally crack the DeCSS for archival purposes, anyone can unlock their cell phone, old software can be cracked, and blind persons can unlock protected ebooks for audio readers (copyright.gov/1201).

Not bad, but we're just getting started. We can't let up - things will change for the better. Getting the information out there - pervasive and complete - eventually makes any effort to silence the critics useless.

We're told there is nothing to worry about with RFID, that it's required for our passports and everything is going to be O.K.

Turns out there are major issues. It only took a couple of open-hardware projects to show how easy it was to clone, even from a distance, an RFID enabled passport. A minor concession was planned - a metallic lining to protect the RFID chip from being read. It's essentially a tin foil hat, go figure. The RFID chip will be encrypted so it can only be read when it's swiped. So what's the point of using RFID? While the battle rages on anyone can build their own reader, cloner, and capturing device (cq.cx/proxmark3.pl). Code and schematics are included.

Cities and large companies (Google) are\ actively seeking to cover every square inch with Wi-Fi. Extremely convenient, sure. But so is broadcasting your ID with RFID chips.

Conveniences that give up privacy aren't always worth the trade. Maybe it will all work out and our data will be safe, it will never be abused, and unicorns will graze on the fields as we live blissfully. What's more likely to happen is tracking, data mining, and incredible breaches of personal information and security. But when your cities are filled with the signal, there isn't really a way to stop it even in your home or business, right? Maybe not.

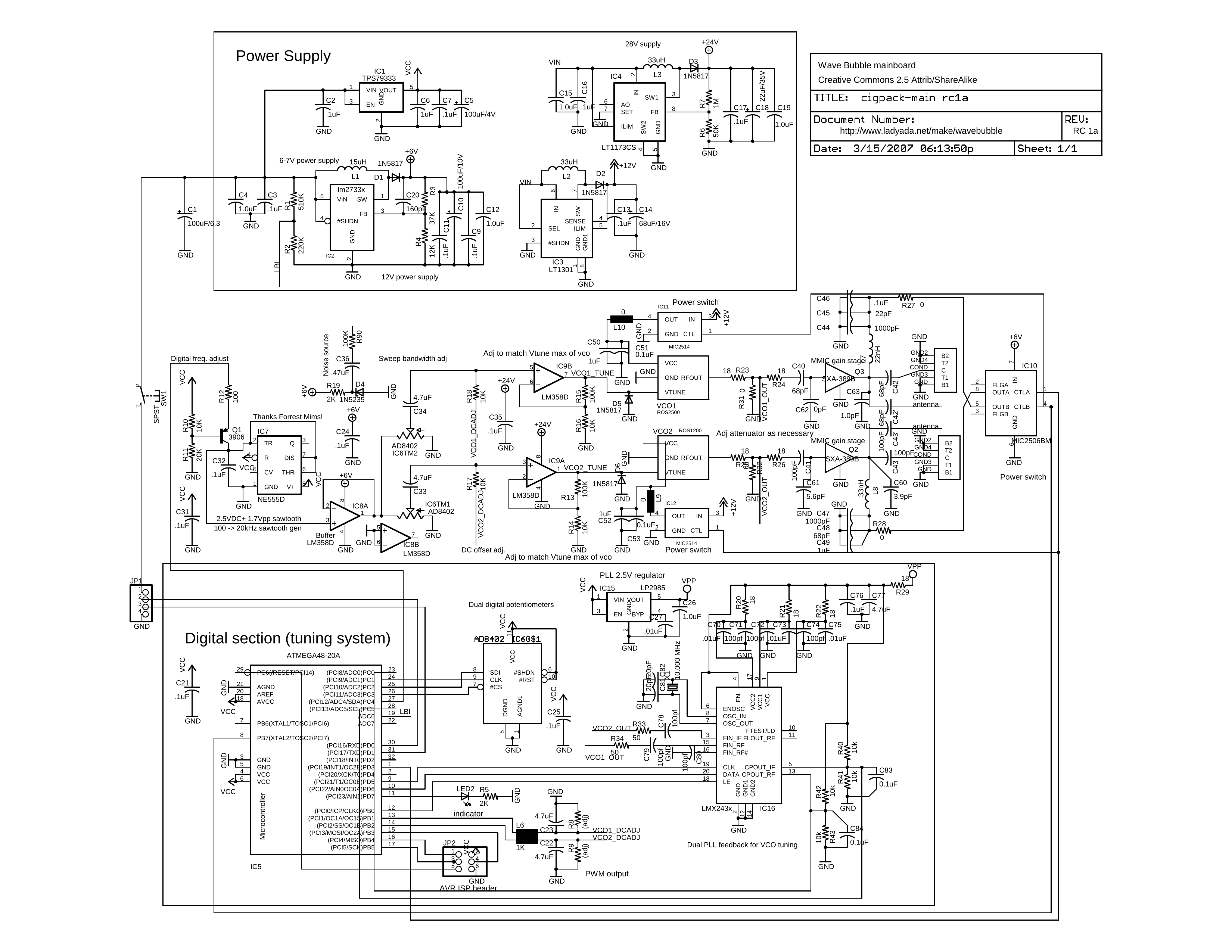

In this issue of 2600 is the circuit diagram and information to build the world's first open-source cell phone and Wi-Fi jammer (ladyada.net/make/wavebubble). The project was created by Ladyada and supported by Eyebeam in collaboration with the cDc.

The project details the design and construction of a self-tuning, wide-bandwidth, portable RF jammer (870-894 MHz, 925-960 MHz, 1805-1880 MHz, 1930-1990 MHz and 2400-2483 MHz - 802.11b/g).

While movie theaters and churches lobby to get cell phone jammers legalized for their own uses (but not for "regular folks"), it's now possible to at least have a chance of having the same capabilities our future nannies will have over us.

There's a whole slew of sayings that start off with "It's better to have it and not need it than need it and not have it." They usually refer to nuclear weapons, voltage, parachutes, and condoms. But in this case it's something that might be just as important.

At the time of this writing a Freedom of Information Act request revealed the approval of the "Active Denial System" or ADS. This weapon is certified for use in Iraq and uses 95 GHz (3 mm wavelength) waves to "inflict pain" on humans (tinyurl.com/y8ap66). The effects are said to feel like being dipped in molten lava. This is incredibly scary stuff.

Wouldn't it be good to know it will never be used against innocent populations? There's only one guarantee. Someone will need to release the information on how to stop it. It's not ripping DVDs, or using a mod chip in an Xbox, or even jamming cell phones to keep calls out of your home. But TASERs and rubber bullets have been abused. What's to stop this?

Who knows?

Maybe the cell phone/Wi-Fi jammer will end up in the computer museum 20 years or so from now as a footnote in the history of subversive technology that led to many many other innovations.